Welcome to Israel Antiquities Authority

Survey WebSite.

The sites documented in the Archaeological Survey of Israel are published on the website where they are displayed in survey squares of 100 sq km (10 × 10 km). The list of maps is presented below in alphabetic order, according to their names and numbers as recorded in Yalquṭ Ha-Pirsumim. The survey maps can be seen on the right side of the screen against the background of an aerial photograph. The sites (marked with yellow dots) can be accessed by zooming in on the screen and a description of them will appear by clicking on the dots. The introduction to each map and search options are also displayed.

-

Afula

Afula

(

33)

Avner Raban and Noy Shemesh (introduction)

978-965-406-535-1

-

Ahihud

Ahihud

(

20)

Gunnar Lehmann and Martin Peilstöcker

978-965-406-259-6

-

Akhziv

Akhziv

(

1)

Rafael Frankel and Nimrod Gerzov

965-406-024-8

-

akko

akko

(

19)

978-965-406-647-1

-

Amatzia

Amatzia

(

109)

Yehuda Dagan

965-406-195-3

-

'Amqa

'Amqa

(

5)

Rafael Frankel and Nimrod Getzov

978-965-406-263-3

-

Ashdod

Ashdod

(

84)

Ariel Berman, Leticia Barda and Harley Stark

965-406-174-0

-

Ashkelon

Ashkelon

(

92)

Alen Mitchell

978-965-406-657-0

-

Ashmura

Ashmura

(

15)

Moshe Hartal and Yigal Ben Ephraim.

978-965-406-468-2

-

'Atlit

'Atlit

(

26)

Avraham Ronen, Ya'acov Olami

978-965-406-361-6

Welcome to the Archaeological Survey of Israel Website of the Israel Antiquities Authority

Following the establishment of the State of Israel, Dr. Shmuel Yeivin, first director of the Antiquities Department, suggested to Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion that “an archaeological survey of Israel be conducted for future generations to know what is concealed within the borders of the new state”. In July 1964, the “Archaeological Survey of Israel” was established as an association. The association’s teams of archaeologists surveyed thousands of sites throughout the State of Israel, many which were new. The results of the surveys are published here in the website, in addition to the many surveys that were carried out as part of the development processes in the State of Israel.

Since 2007 the Archaeological Survey of Israel website has been the publication platform of the surveys performed by the Israel Antiquities Authority. The survey maps that were published as books appear in the site together with the dozens of survey maps added in recent years. The maps include geographic and archaeological introductions, descriptions of ancient and historical sites, illustrations, plans, periodic maps and bibliography. The sites are displayed in survey squares of 100 sq km (10 × 10 km).

The list of maps is presented below in alphabetic order, according to their names and numbers as they appear on the general map on the right side of the screen. The sites (marked with orange dots) can be accessed by zooming in on the screen and their description will appear by clicking on the dots.

Loading Survey Point Data ....

Introduction to the Golan Survey

Moshe Hartal

Preface

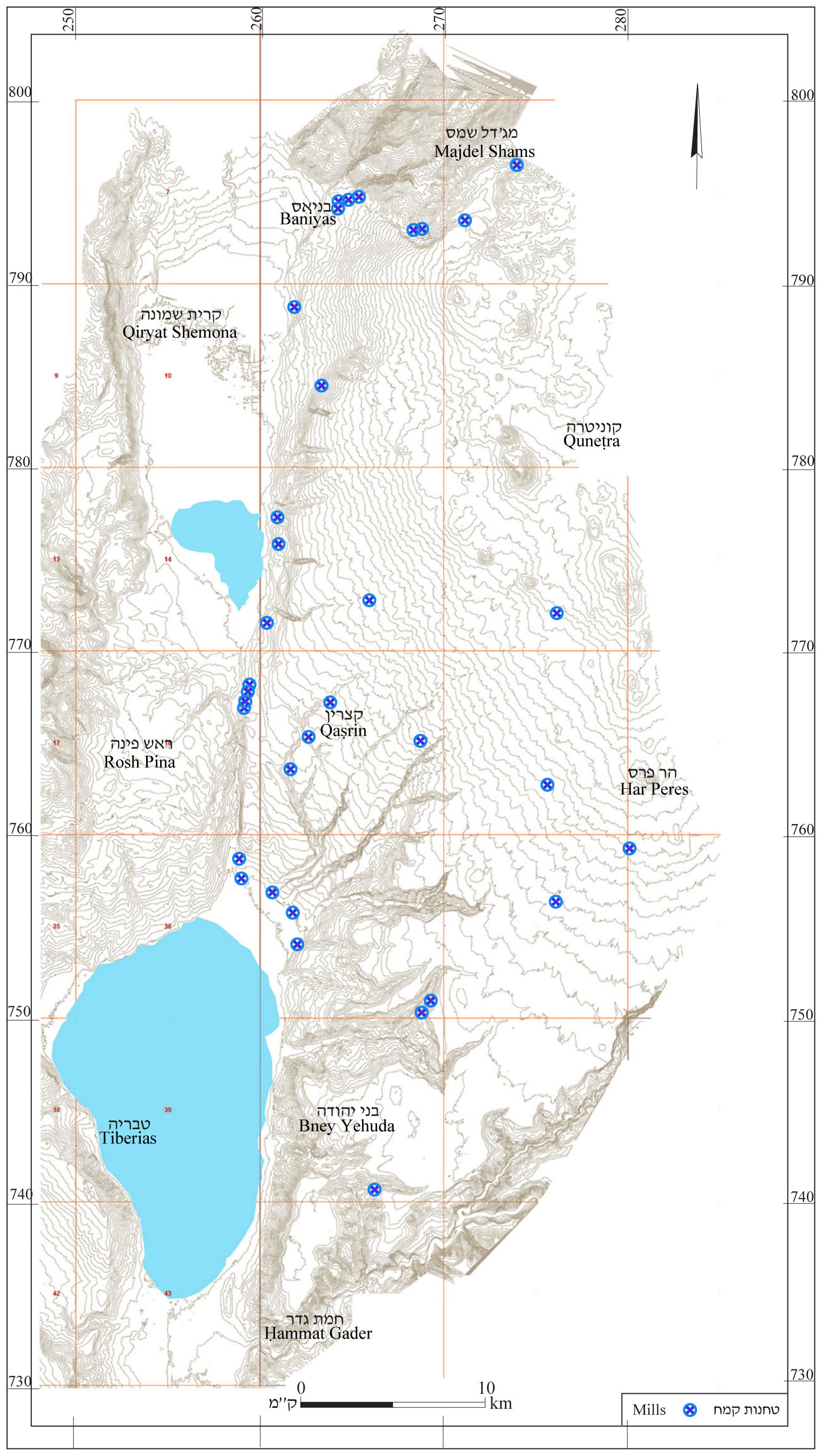

Sixteen surveys have been or will be published that cover the Golan and Mount Hermon within the area of the State of Israel. They are: Ḥammat Gader, ‘Ein Gev, Nov, Ma‘ale Gamla, Rujem el-Hiri, Giv‘at Orḥa, Qaṣrin, Qeshet and Har Peres. The following surveys are in preparation: Ashmora, Har Shifon, Shamir, Merom Golan, Dan, Birket Ram and Har Dov.

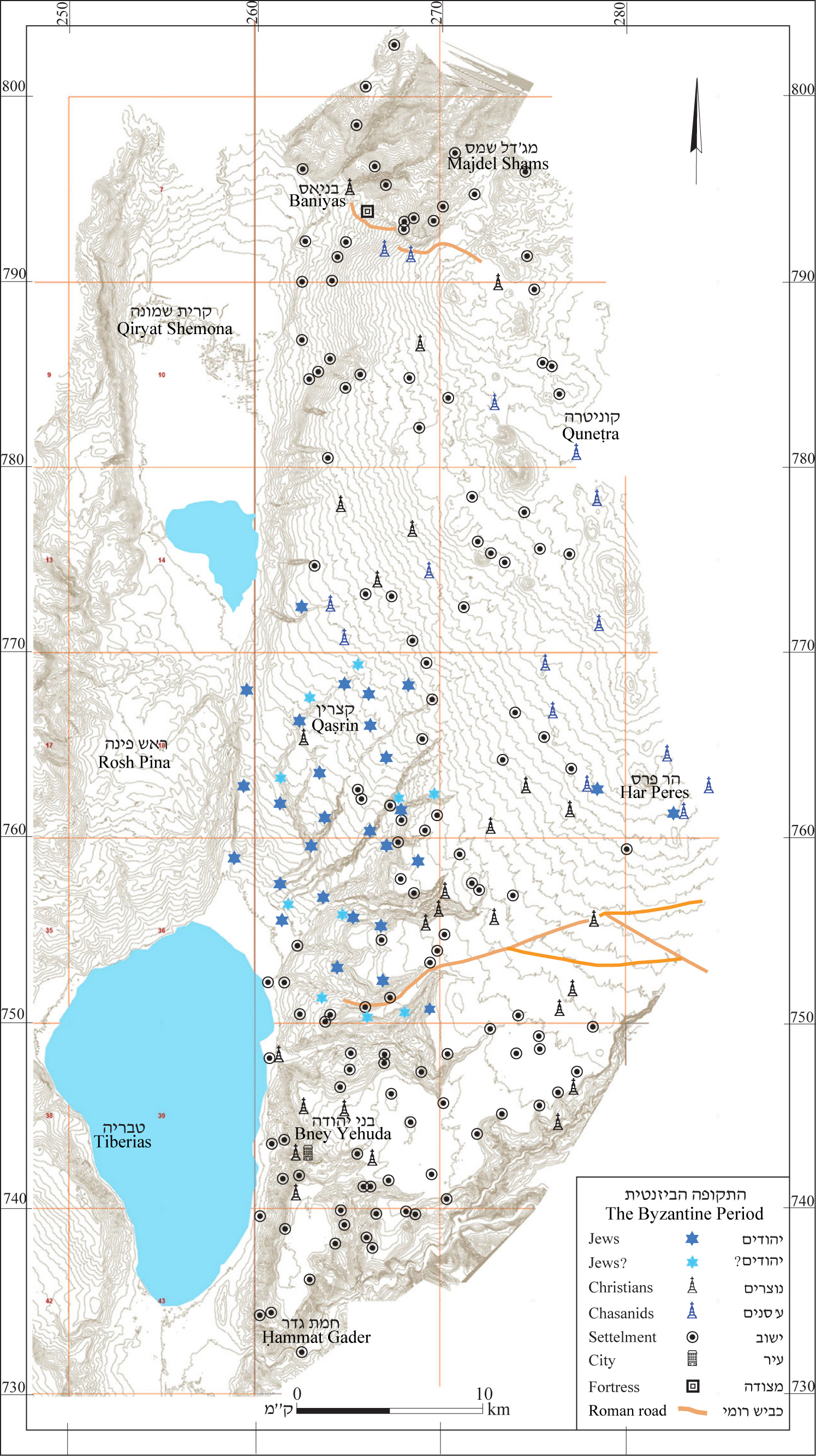

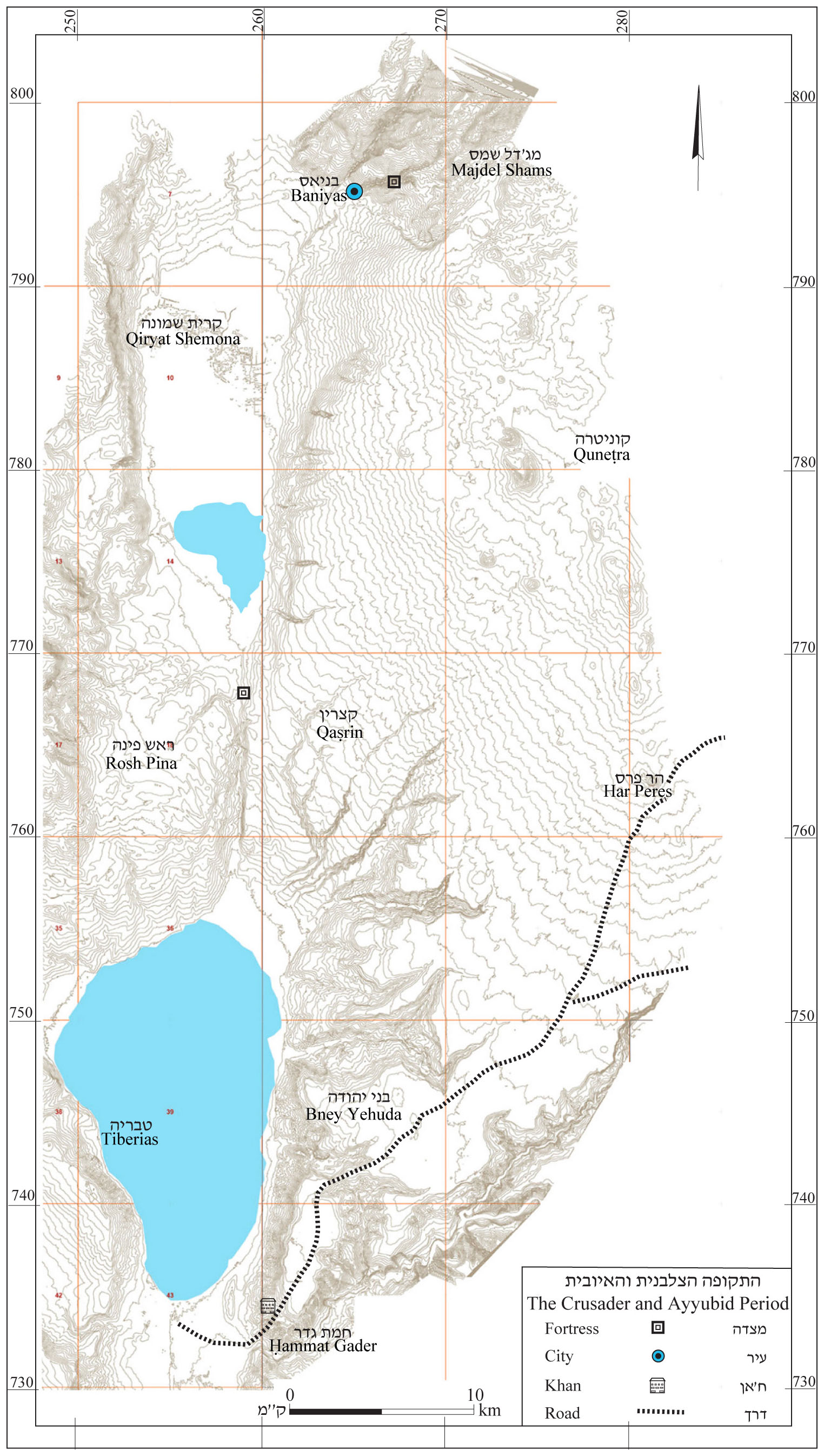

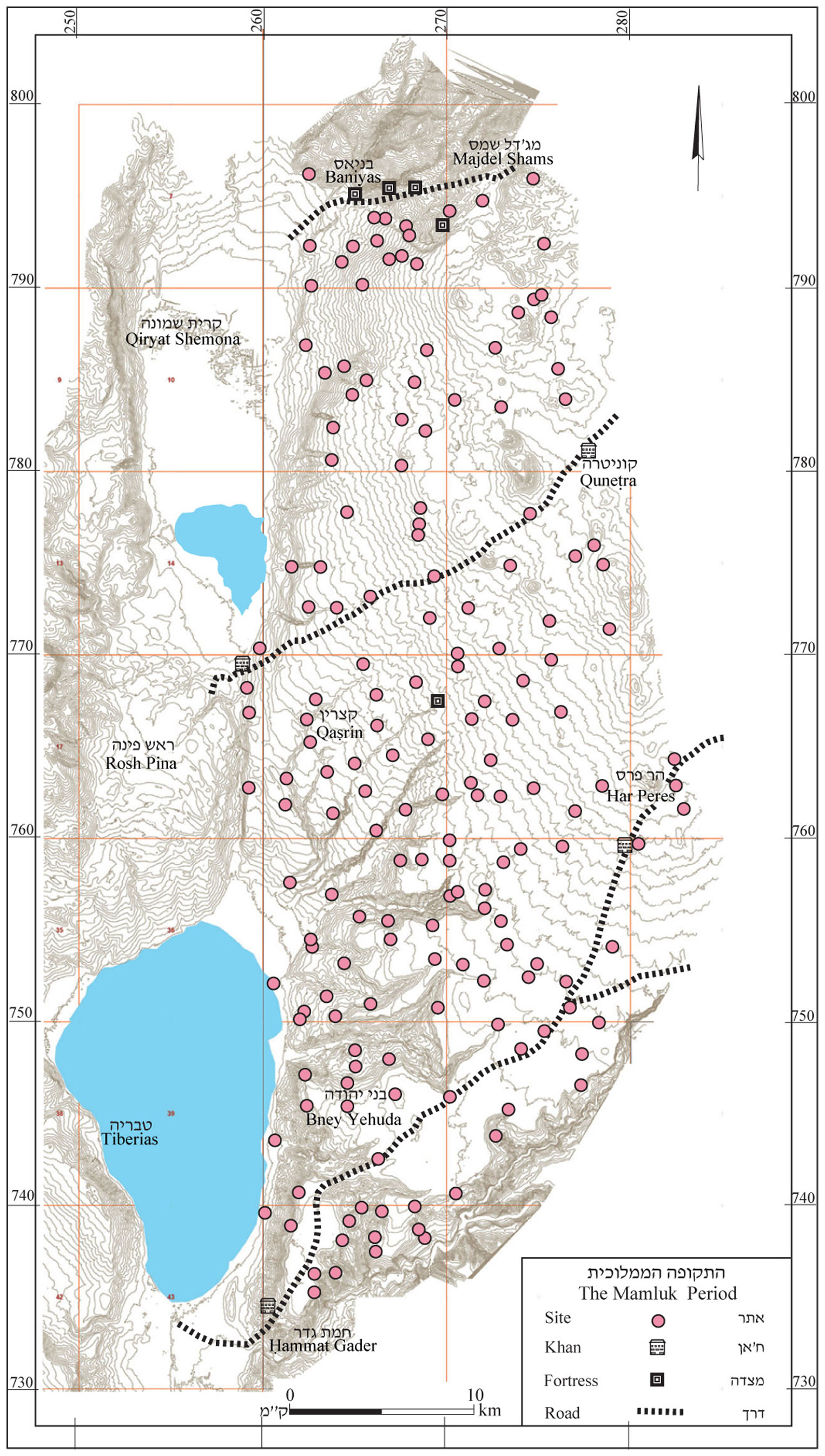

As is customary, each survey comprises an independent unit, in each of which the sites and findings are described. Each individual survey includes a geological introduction and a description of the history of settlement in the various periods. The information is accompanied by detailed maps of the periods.

However, the nature of the publication is such that it presents a fragmented picture due to the arbitrary division of the maps, a picture that does not correspond to landscape units or settlement distribution. That is the reason for this general introduction, which provides a full picture of the entire region in the various periods. The maps of the periods appended to the introduction, highlight and emphasize the dynamics of settlement over the generations in the entire region.

Because the historical background of each area is presented in the individual surveys, to avoid repetition, I have made do with a brief description of the events there, and refer readers to this introduction, which expands on the historical and archaeological sources for the history of the Golan.

The bibliography contains the main research sources on the Golan, where interested readers can find additional information and details that go beyond the scope of this publication.

Editor: Ofer Sion

Text Editing: Ruti Erez Edelson

Table of Contents

Preface

1. The History of the Research

The Golan was first surveyed between 1884 and 1886 by Gottlieb Schumacher, who created the region’s first detailed map (Schumacher 1888). Schumacher carried out his survey at a time when the archaeology of the Land of Israel was still in its infancy and the use of pottery for dating sites was still unknown. Thus, the information that can be gleaned from this survey is fairly limited. The importance of Schumacher’s survey is that it was the first, and particularly because of the description of the Golan at the end of the 19th century, a period in which the Bedouin tribes had begun to settle down.

At the time of Schumacher’s survey, in 1885, Sir Lawrence Oliphant also surveyed a number of sites in the Beteiḥa (Bethsaida) Valley in the southern Golan. Among these sites are Khisfin, the synagogues at Umm el-Qanaṭir, Khirbet ed-Dikke and el-Ḥuseniyye (Oliphant 1884, 1886).

A large cemetery, dated to the Roman and Byzantine periods, was excavated in 1936 at Khisfin by "a team of excavators headed by Prince Mijem

el-Shalan of the ‘Annezzeh bedouin tribe”; which seemed more like grave robbery. Six years later, additional tombs were uncovered with the assistance of antiquities merchants, the Dahdah brothers.

The Syrian Department of Antiquities worked to save the findings from the tombs. Findings from 54 tombs are documented in the National Museum in Damascus, each apparently a single burial. Unfortunately, because of the nature of the excavations, there is no information about the precise location of the tombs, their structure, the find-spots of the artifacts and of the human remains (Weber 2006:64).

Four figurines from Khisfin on display at the National Museum in Damascus were published by T.R. Weber (2006:64–68). In 1942 and 1962, excavations were carried out at Fiq and el-‘Āl, but none of the findings were published (Dentzer 1997:89).

In 1968, the Golan was surveyed by two teams headed by Claire Epstein and Shmariya Guttman (Epstein and Guttman 1972). Epstein and Guttman continued their surveys in 1969, discovering additional sites; however, these surveys were not published. These surveys were undertaken during the first period of re-acquaintance with the Golan, at a time when some of the characteristics of the region were unknown. They focused on villages and ruins and did not cover the entire area. The publication of the first stage of the survey does not deal with the environmental conditions, while, as noted, the second stage was not published at all.

From 1968 to 1970, dozens of sites were examined in the survey of abandoned Syrian villages under the direction of Dan Urman. Emphasis in Urman’s survey was on architectural findings and locating reliefs and inscriptions. Almost no pottery was collected. The survey was never published, but it served as raw material for Urman’s book (1985).

Meanwhile, Yitzhaki Gal conducted a site and landscape survey, in which he described many sites (Axelrod 1970). From 1983 to 1987 Moshe Hartal conducted an extensive survey of the northern Golan, where numerous sites were discovered and a fuller picture emerged of the development of settlement in the region from prehistoric times to the present (Hartal 1989).

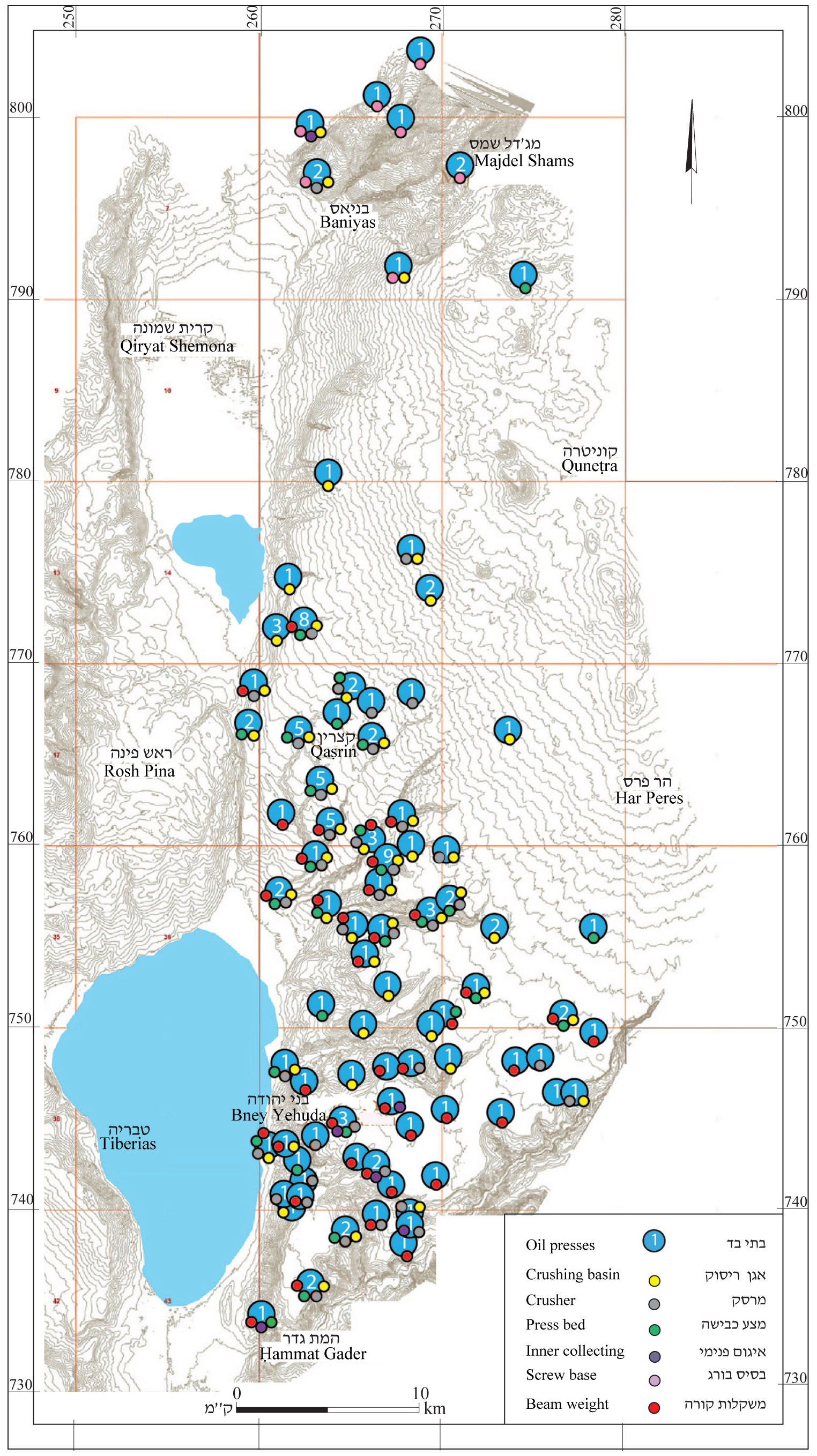

The Mount Hermon sites were surveyed from 1983 to 1989 by Shimon Dar (1978; 1993). Some of the surveyors focused on a certain subject or number of subjects in this area. C. Epstein surveyed and excavated dolmen fields (Epstein 1985) and sites from the Chalcolithic period (Epstein 1998). The synagogues were surveyed by Z.U. Ma‘oz (1981, 1995) and Zvi Ilan (1991: 61–113). Chaim Ben David (1998) surveyed the Golan’s oil presses, excavated ‘Ein Nashôt and Giv‘at HaYe‘ur and also surveyed the Jewish settlements in the lower Golan (Ben David 2005). A survey of the Byzantine villages was conducted by C. Dauphin and S. Gibson (1992–1993). Partial surveys were conducted by A. Golani (1990) and L. Vinitzky (1995). O. Zingboim (2001) surveyed ancient cemeteries in the southern and central Golan. He also conducted development surveys in various places in the Golan. S. Friedman surveyed settlement sites in the southern Golan (still unpublished).

Hundreds of inscriptions were revealed by the various surveys; most were on tombstones. Others included dedicatory inscriptions – on buildings, milestones and boundary stones. Urman published the Hebrew and the Aramaic inscriptions (1984, 1996) and a selection of the Greek inscriptions were published by Gregg and Urman (1996), C. Dauphin (Dauphin, Brock, Gregg and Beeston 1996) and L. Di Segni (1997).

In 1993, then-director of the IAA, Amir Drori, initiated a survey in the central and southern Golan in order to complete the methodical survey of the Golan. The Survey was headed by M. Hartal, district archaeologist of the Golan at the time. The southern Golan was surveyed by a team headed by H. Bron and E. Kelmachter (1997). The team surveying the southeastern Golan was headed by D. Goren and Y. Ben-Ephraim headed the team that surveyed the central Golan (1997). Participants in the field survey were R. Bar-Nur, A. Elrom, Y. Sheffer, I. Abu-Awad and V. Bar-Lev, with C. Epstein, O. Marder and M. Hartal acting as advisers. The field survey took place from 1993 to 1998 and was completed in 2001 by M. Hartal and R. Bar-Nur. Y. Ben-Ephraim coordinated the findings of his surveys with those of the southern teams, but the material did not reach the publication stage.

In 2010, I was given the task of publishing the survey. Since much time had passed since the conclusion of the work, and there were previous surveys that had not been published, I decided to publish most of the information that had been collected about each site in surveys conducted in the Golan over the past decades.

In preparation for publication, more than 20,000 pictures taken during the surveys were scanned, from the first surveys by Epstein and Guttman and to the present. Some sites were re-photographed. The manuscripts of the unpublished surveys were also gathered, including phase 2 of the Epstein-Guttman survey, the village survey directed by Urman and Golani’s survey. I once again went over all the pottery that had been collected in the various surveys and I prepared the pottery tables for each site whose findings justified this. The publication is based on the notes of Y. Ben-Ephraim, which were completed according to other surveys. The prehistoric sites were described by O. Marder.

2. Geography of the Region

2.1 Northern Transjordan

Northern Transjordan is covered with basalt flows, some of which rise as cones of volcanic ash; however, they are not uniform; a number of different areas can be seen, each with its own characteristics.

2.1.1 The Golan Heights – a plateau extending from the foot of Mount Hermon in the north to the Yarmuk River in the south and between the Jordan River in the west to the Ruqqad River in the east. In the northeast, the plateau reaches a height of 1,000 m above sea level, and the ash cones rise to a height of 1,200 m and more. It slopes gradually southward to a height of c. 300 m. On the west it is bounded by the steep slopes descending to the Hula Valley, the Jordan and the Sea of Galilee, which are approximately 200 m below sea level (see below, 2.2)

2.1.2 Naqura – East of the Golan a broad plateau, 500–700 m above sea level, extending as far as Jebel el-Druze. The basalt covering of the plateau has eroded and created large areas of fertile agricultural, soil, low in stones, especially suited for the cultivation of cereals. Wadi a-Zidi is the southern boundary of this area. It passes north of Boṣra and enters the Yarmuk northwest of Dar‘a. The northern border is Wadi a-Dahab, which emerges from the southern edges of the Leja (see below 2.1.4). Jebel el-Druze (see below 2.1.5) and the Leja are the boundaries of Naqura on the east and the north. West of Leja the Naqura Plateau extends northward to al Sanamayn. To the south, it gradually merges with the Jordanian desert. Due to the relatively low precipitation (200–350 mm per year), water is the main problem for settlement in large parts of this region.

2.1.3 Jadur – northwest of el-Sanamayn Jadur is the name of the land that rises gradually to a small lava field at the foot of Mount Hermon. It differs from Naqura in its rocky ground and its altitude – 600–900 m above sea level. Volcanic ash cones, such as Tell el-Mal and Tell el-Ḥara, rise as much as 1,000 m above sea level. This area is largely an extension of the landscape unit of volcanoes and valleys of the northern Golan (see below 2.2.8).

2.1.4 Leja – an area of approximately 1,000 sq km between Shahaba, Buraq and Izra‘a, covered with fissured basalt almost without soil; the basalt creates alternating scatterings of large boulders and irregular basalt mazes. The area looks like a desert, but it served as pastureland and a hideout for highway robbers. In the southern part of the Leja are a number of basins of fertile agricultural soil without rocks. The settlements in this area are divided between those on the perimeter of the Leja, which enjoy protection and the fertile soil (el-Mismyah, Buraq, Dakir, Khalkhala, Shahaba, Najran, Azra‘, Khabab, and others) and those within the Leja, mainly in the south near the fertile basins (Damiat el-‘Alyam, ‘Arieka, Jarin, Lubin, Ṣuar and others).

2.1.4 Jebel el-Druze (Jebel el-‘Arab, Mount Ḥawran) – created from an accumulation of basalt flows rising about 1,000 m above sea level, and a peak of 1,860 m. The level area on the peak extends over an area of 30 x 60 km. The almost flattened peak, at a height of 1,500 m, is located in the northern half, and is surrounded by many ash cones. The steeper slopes of the mountain are located on the eastern and western sides, with fertile, arable soil. Because of its height, the mountain is forested and has abundant water at the top. Its slopes are the eastern extent of permanent settlement in the lava country and they create the boundary between the “desert and the sown.” South of the peak plain the slopes are more moderate and they descend to the plains of Tzalhad and Boṣra and south to Umm el-Jimal. This area is sometimes called “southern Ḥawran” and it is suitable both for grazing and winter crops. The western part of Jebel el-Druze is rainy and utilized for agriculture. The western slopes, at 1,000-1,300 m above sea level, feature a band of oak forests. Grapes and fruit trees can be cultivated from 950 m to the peak, while cereals and legumes are cultivated on the slopes. South and east of the mountain the area is suitable for sustaining nomads only.

2.1.5 eṣ-Ṣafa and Ḥara – East of Jebel el-Druze is a broad region, covered with basalt flows. It is arid, with an annual rainfall of only 200 mm, which declines as one moves east. In most periods nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes made their homes there. Seasonal agriculture is possible in the streambeds and in the portions nearer to Jebel el-Druze (Ard el-Bataniya).

2.2 Landscape Units of the Golan Heights and Mt. Hermon

The survey was conducted in two different geographical regions: the Hermon and the Golan. The character of the Hermon greatly differs from that of the Golan. The Hermon is mountainous, and consists mainly of sedimentary rock, while the Golan is a plateau covered with volcanic rock. Because only a small part of Mount Hermon is within the boundaries of the State of Israel, and because it was surveyed at the same time as part of the Golan Heights survey and revealed evidence of cultures similar to those of the northern Golan, both of these regions were included in the survey. The following aspects will be described below: landscape units, geological and climatological characteristics and their impact on human settlement in the various periods (see map 1).

2.2.1 The Hermon – the southern part of the Anti-Lebanon range. The ridge is c. 50 km long and c. 25 km wide and its highest point is 2,814 m above sea level. The Hermon, which is built mainly of limestone and dolomite, is largely a broken anticline, both on its edges and within it. The limestone and dolomite of the Hermon date from the Jurassic period (170 million years before present). Two parts of the Hermon ridge are included within the State of Israel the Shiryon spur in the east, whose peak is snow-covered, at a height of 2,121 above sea level; and the Sion spur in the west, whose highest point is 1,548 m above sea levels. Naḥal Sion separates these two areas.

The stream pattern in the region (the Naḥal Sion and Naḥal Govta, among others) was determined mainly by the geological faults. Lacking springs with regular flows, the streams are seasonal, their flow dependent on the extent of melting snow. The higher area – above 2,000 m above sea level, is snow-covered for most of the winter. Rainfall is greater here than anywhere else in the country, reaching an annual average of 1,600 mm in part of the highest area of the mountain. Karstic activity is prominent in the landscape, appearing in two main phenomena – dolinas and numerous rills and gullies.

The thin vegetation is apparently the result of human intervention, by deforestation and over-grazing. In the high zone (above 1,800 m above sea level) the dominant vegetation is alpine.

Settlements developed on the Hermon only in the area under the snow line. Small villages and farms were built in this area, whose inhabitants cultivated small plots in the valleys or on top of the spurs. Due to the forested nature of the area, the soil potential and the severe climate, the Hermon was inhabited only during periods of intense settlement.

Settlements in the area were first established at the beginning of the Roman period and were abandoned at the beginning of the Byzantine period. After hundreds of years of abandonment, a number of ruins were re-inhabited at the end of the 19th century or the 20th century, mainly by seasonal settlements of the neighboring villages.

2.2.2

Baniyas Plateau – A plateau 300–450 m above sea level, constituting an intermediate step between the Golan and the northern Hula Valley. The plateau is cut by the Naḥal Sa‘ar. This area is covered with basalt, on which shallow, lithosol basalt soil was created.

The surface declines toward the Hula Valley in two natural terraces, whose western slopes are particularly steep. This phenomenon is particularly prominent at Mitṣpe Golani and Giv‘at ‘Azaz. The main water channel in this area is the Naḥal Pera‘, to which a number of large springs drain, the largest of which are ‘Ein Abu Suda and ‘Ein ‘Azaz. A forest-park of Mt. Tabor oak, which in the past covered the whole area, was largely decimated and replaced with Ziziphus lotus and herbaceous species. Due to the relative low elevation of the Baniyas Plateau, the climate is moderate.

2.2.3

‘Ein Quniyye Hills – A hilly region 400–880 m above sea level covering c. 6 sq. km. Spurs consisting of sedimentary rock are typical of the area. These spurs constitute intermediate terraces between the Baniyas Plateau on the west and Har Qeṭa‘ in the east.

The northern part of the region consists of hard limestone of the Hermon Formation. These rocks create the Nimrod Fortress Spur. This spur, which bounded on the north by the Naḥal Govta and on the south by the Naḥal Naqib, descends gradually to ‘Ein Pamias. The spur is very rocky and is uncultivated in the main. Over time, brown-red terra rosa soil developed on it. Olive groves are now planted on the southern, moderate slope of the spur, while thick natural woodlands grow on the northern, steep part. Dwarf-shrub steppe grows in areas were the natural woodlands have been decimated. The Nimrod Fortress was built atop the spur and a fortified encampment was established to its east.

The area south and east of the Nimrod Fortress spur is built of soft marl rocks and limestone. The soil created on top of them is light rendzina – undeveloped and relative poor. The areas covered with this soil were once utilized to raise winter cereals.

In other parts of the area light-brown rendzina soil was created. This soil is developed and rich in organic material. It is cultivated, particularly on the slopes below the village of ‘Ein Quniyye, where orchards of deciduous species, olives, figs, pomegranates and prickly pear have been planted. Small plots are used to grow vegetables and in the past, they were also used to raise tobacco. A good many of these areas are irrigated with spring water, which emerges at relatively high altitudes and therefore is easy to use for irrigation.

The layers of marl created many large and small springs, which emerge at the eastern edges of the region. There are 18 springs in the village of ‘Ein Quniyye, some in the ‘Ein Quniyye Hills. The largest of these are ‘Ein a-Shalala (1.1 million cu m of water per year) and ‘Ein Ḥammam (23,000 cu m of water per year).

The entire area is drained by two streams – Wadi Naqib and Masil ‘Eisha. Wadi Naqib creates a deep, steep channel south of the Nimrod Fortress. The wadi passes through very porous karstic limestone, and therefore, other than a number of instances of flooding, hardly any water flows through it on the surface.

Masil ‘Eisha with descends from ‘Ein Quniyye in the southern part of the area and passes through marl rocks and therefore the valley created here is broader. The stream flows throughout most of the winter and spring, and when the water of ‘Ein Ḥammam, which feeds the stream, is not diverted for agriculture, it flows in summer as well. This was apparently the situation during the Roman period, when the stream provided water for an aqueduct that led it to the nearby city of Paneas.

There were once a number of small settlements in the area. Today the Druze village of ‘Ein Quniyye is located there.

2.2.4 Har Qeṭa‘ – Built of a band consisting of a series of broad, flat terraces, created between layers of sedimentary rock. The area is located between ‘Ein Quniyye on the west and Ya‘afuri Valley on the east. In this band, which is 2 km wide and has an area of c. 10 sq km, dolomite rocks were found, along with sandstone, marl and shale from the Cenomanian Phase and the Lower Cretaceous and Jurassic periods. Among the sedimentary rocks remnants of ancient volcanic eruptions can be seen, from the Lower Cretaceous period.

The varied geological structure can also be observed on the surface. The alternating hard and soft rock and the incline of the strata create an elongated ridge on a northeast–southwest axis. Its peak, at 1,173 m, is located southwest of the town of Majdal Shams. The ridge descends in a series of terraces via Har Qeṭa‘ (1,115 m above sea level). On the peak of Har Qeṭa‘ is the community of Nimrod and the site of Khirbet el-Ḥawarit (1,020 m above sea level).

This ridge is surrounded on all sides by steep slopes: to the south above the Naḥal Sa‘ar, to the west above ‘Ein Quniyye, on the northwest above the Naḥal Ḥazur and to the northeast above the Ya‘afuri Valley. Small streams emerge on these slopes due to the layers of marl. Atop the sandstone is ḥamra soil that has eroded down. This soil is quite poor and therefore until recently most of the ridge was not cultivated and was covered with dwarf-shrub steppe and annual vegetation. There is also much less pasturage on the ridge than in the basalt areas to the south. In recent years, plots have been created for cultivation by the Druze by adding soil brought from other areas, which has made possible the cultivation of cherry and apple trees in large areas.

This area, which, as noted, was soil-poor, was almost unsettled throughout history. The main settlement here was Khirbet el-Ḥawarit, which is located near springs and a valley that could be easily cultivated. The inhabitants of this area utilized the marl and sandstone, creating manufacturing center for pottery. The workshop from the Roman period found here is a link in the chain of pottery production that began in the Early Bronze Age and continues at Rashia el-Fuḥar to this day.

2.2.5 Ya‘afuri Valley – triangular in shape, with its base at Birket Ram and its apex at at ‘Ein Sa‘ar. It is c. 2 sq km in area. The upper portion of the perennial Naḥal Sa‘ar passes through the center of the valley. The average annual flow volume of ‘Ein Sa‘ar is 6.47 cu m. ‘Ein Mushreifa (annual flow volume 1.6 million cu m) emerges on the eastern edges of the valley. Smaller springs – Neba‘ Sa‘ar – also emerge on the western edges of the valley.

The valley is covered with a thick layer of brown Mediterranean accumulative soil – young soil that eroded and collected in the valley and is suitable for field crops and orchards. Today the valley and its slopes are planted with deciduous species. There are currently no settlements in the valley but in the past there were three. The largest of these – Khirbet Sa‘ar – was located in the middle of the valley. The two smaller sites are on the eastern edge of the valley – Khirbet el-Baqi and an unnamed ruin found recently on the border with Syria. The tomb of Nebi Ya‘afuri, who is a sacred figure to the Druze, is located in the valley, hence, its name.

2.2.6 Har Ram – A mountainous area of c. 6 sq km, which rises east of the Ya‘afuri Valley, where sedimentary rocks are exposed from the Cenomanian to the Eocene. A good deal of the area consists of dolomite rock; but on the southeastern and northeastern edges limestone, chalk, marl and flint were also exposed. The upper part of Har Ram is built of cover basalt, much older than the basalt of the northern Golan.

Three mountains rise in this area: Sḥyta (1,127 m above sea level), Ram (1,202 m above sea level) and Tell el-Manpukha – the highest of them all (1,210 m above sea level), and the highest peak in the region in general. Between the mountains are small, arable valleys. The region is drained mainly to the west, by seasonal streambeds that pass through the valleys and drain into Wadi el-Shar‘ani and the Naḥal Sa‘ar.

Terra rosa and rendzina soils were created on the sedimentary rock, while on the basalt slope, lithosols were created – young, poor soils, which are typically very stony and suitable only for grazing.

Brown Mediterranean soils accumulated in the valleys, which are suitable for field crops, and in places where the soil is deep, for orchards as well. This area has been prepared for cultivation by the Druze and numerous deciduous orchards have been planted there. The only community in the area was the Druze village of Sḥyta, which was built on an ancient site. This village was abandoned after the Six-Day War and its inhabitants moved to nearby Mas‘adeh.

2.2.7 Odem Flow – A very dominant landscape component in the northern Golan. This extensive area is covered with basalt flows from the foot of Mount Odem and flowed west to the Hula Valley, north to the Naḥal Sa‘ar, east to the Buq‘ata Valley and south to the Quneṭra Valley.

The area is completely covered with flows of ‘Ein Zivan-type basalt. These flows create rocky, stepped plains covered with poor soil and large quantities of rocks. A number of ash cones protrude from it, the largest of which is Mount Odem. In the western part of the flow are a number of large craters (“jubas”), which were created by volcanic eruptions.

There are hardly any water sources in the area of the flow. Except for two small springs, most of the springs emerge along its edges. The combination of poor soil and lack of water turned the Odem Flow into the one with the low settlement potential of the entire Golan (see below, Chapter 3). Indeed, throughout most periods there were no settlements here at all. Only in the Late Roman and the Byzantine period were the first settlements built here, as part of the extensive work of preparing land for cultivation and the digging of wells and cisterns. During this period the Odem Flow saw only two settlements: Sukeik and Ra‘abne. Other settlements, including Bab el-Hawa, were built on the edges of the flow, taking advantage of the springs in that area and the nearby soil.

Most of the area of the Odem Flow is above 700 m above sea level and consequently the climate is cold, the winds are strong, and snow falls almost every year.

2.2.8 The Volcanos and the Valleys – These extinct volcanoes, with fertile valleys in between them, are located on the basalt plateau. The ash cones of the volcanos consist of scoria and tuff. They are arranged in two parallel lines on a northwest–southeast axis. On the slopes of the ash cones the soil is of the tuff regosol type – shallow and suitable only for grazing; and Mediterranean tuff soil – intermediate soil; usually deep and suitable for all crops, including orchard species. The slopes are covered with herbaceous species and shrubs and in a number of places, patches of woodland species. Vineyards and fruit orchards are planted on the lower part of the slopes.

The ‘Ein Zivan lava flows emerged from the ash cones (see above, 2.2.7). The flows are densely covered with woodland species – oak and terebinth, which survive to this day; because the area was mainly used for grazing and was little farmed. In the areas between the ash cones, which were not covered with young ‘Ein Zivan basalt, valleys were created where Muweisse basalt was exposed, on which brown, basaltic Mediterranean soil was created with few rocks. Soil of this type is good for agriculture and suitable for most crops. In contrast, on the slopes of the hills surrounding the valley the soil eroded away and the remaining poor soil is found in fissures and pockets between the rocks and is not arable.

As noted above, the valleys are arable and the settlements were usually concentrated on their edges. The most important of these valleys are: Wadi Abu Sa‘id; the Buq‘ata Valley; Marj el-Qatarna and the Quneṭra Valley. The latter is the largest of these valleys. It is 6 km long and 1–2 km wide, with an area of c. 10 sq km. Most of the Quneṭra Valley is covered with tuff, on which tuff regosol developed and red Mediterranean tuff soil – fertile and arable soils. Due to drainage problems a swamp developed in the northwestern part of the valley, which was flooded in winter.

In the southeastern part of the volcanos and the valleys is the Bashanit Ridge. This ridge consists of ‘Ein Zivan basalt on which is a line of ash cones, the central of which is Mount Ḥazak. The ‘Ein Zivan flows emerged from the ridge and covered the areas west and north of it. The soil created on the slopes eroded away leaving behind basaltic lithosol. On the moderate slopes of Bashanit Ridge brown Mediterranean soil accumulated, very stony and difficult to cultivate. For this reason most of the ridge is not cultivated and there are large areas covered with Mediterranean woodland species – Kermes oak and Bossier oak.

At the southern end of the landscape unit are the volcanos of Har Peres and Giv‘at Orḥa. The northern end of the unit consists of relatively young volcanic rock – Kramim basalt and Birket Ram tuff. Sedimentary rock is also exposed there, mainly limestone and chalk. Wadi Abu Sa‘id drains this area, running through its eastern part in a broad valley surrounded by rounded hills with moderate slopes. On the western side, the stream deepens and creates a valley with steep slopes, which flows into the Naḥal Sa‘ar north of Mas‘adeh.

The volcano landscape unit is located in the higher part of the Golan, in the area 700–1200 m above sea level. Most of which is more than 800 m above sea level. Due to the height, temperatures are relatively low, winds are strong and there is a large amount of precipitation (700–900 mm per year), with snowfalls almost every year.

However, despite the great precipitation, water sources in the area are few. Birket Ram is the largest such source, containing 1–5 million cu m of water. However, its geographical location at the bottom of an enclosed crater made it difficult to utilize in the past.

The springs in this unit are few, and most run dry in the summer. Only in the southern part of the unit are springs more plentiful and their flow volume greater. The water table in the northern part of the unit is high and can be relatively easily accessed by digging wells.

2.2.9 The Northern Plateau – descends from a height of 800 m above sea level in the east, at the foot of Mount Avital, to 500 m above sea level in the west. In the west it is bounded by a system of faults that create the slope of the Hula Valley and the landscape unit of the Hula Valley streams. In the north, the plateau is bounded by the Odem Flow (see above, 2.2.7) and in the south it is incorporated into the central plateau, with no clear boundary dividing them.

The northern plateau is covered by Muweisse basalt flows on which good arable soil developed, as well as by Dalawa basalt flows, on which rocky, poor soil developed. Above the basalt plains a number of ash cones rose, the most important of which is Tel Shiban.

On the edges of the Odem Flow, near Wasit and Summqa, springs flow that provided water to the area year-round. Another group of springs is found near ‘Aliyqah and additional springs emerge in the streambeds.

This area has the smallest amount of trees anywhere in the northern Golan. It seems that the area was once covered with a forest-park of Mount Tabor oaks that was decimated long ago.

The climate varies according to height above sea level. The upper part of the plateau is in the snow zone, while most of the area has a more moderate climate.

2.2.10 The Hula Stream Basins – are located at the foot of a steep slope descending from the northern plateau, from 500 m above sea level to the Hula Valley, 70 m above sea level. The streams, which descend from east to west are relatively short (3–7 km) and parallel to each other. In the eastern, higher parts, they flow through shallow valleys; but when they reach the steep slope in the Hula Valley they create deep valleys and sometimes even canyons. These valleys impede north–south movement.

2.2.11 Naḥal Meshoshim and Naḥal Yahûdiyye Basins – located on a flat plateau descending moderately from 500 m above sea level, northeast of Qaṣrin; to the southwest, to a height of c. 130 m below sea level, in the Beteiḥa (Bethsaida) Valley on the shore of the Sea of Galilee.

The area is drained by Naḥal Meshoshim and its tributaries, the largest of which is Naḥal Zavitan. The streams dig deeply and create deep valleys, and in certain portions even canyons. Because of the area’s topographical structure, Naḥal Meshoshim is relatively long – c. 15 km, and flows parallel to the Jordan River, unlike most of the other streams in the Golan.

Naḥal Yahûdiyye flows parallel to Naḥal Zawitan, the former beginning at the foot of the Bashanit Ridge. Upper Naḥal Yahûdiyye and its tributaries flow through shallow valleys; but the lower part of the stream creates a high canyon. The stream channel is narrow and surrounded by cliffs and steep slopes. The streams in the area flow year-round. Precipitation ranges from 600 mm per year in the Qaṣrin area to c. 450 mm in the Beteiḥa (Bethsaida) Valley.

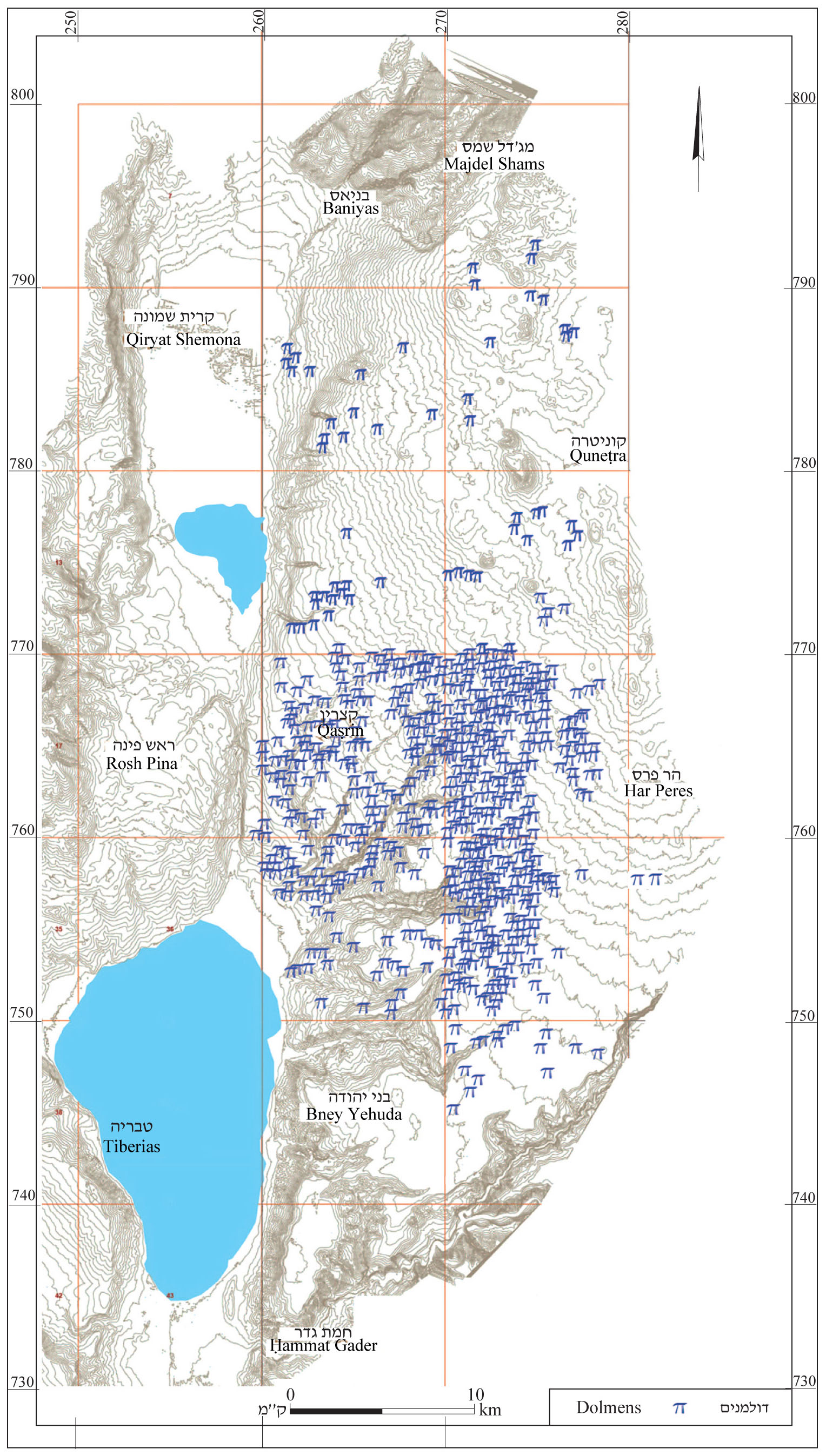

This unit is bounded on the south by a long geological fault – the Sheikh ‘Ali Fault – which caused a drop in the surface to the north. The area is covered mainly with rocky Dalawa basalt, with large quantities of stones and shallow soil. The stones atop the Dalawa basalt were used as building material in the villages, many of which were built on the edges of the region, as well as for dolmens. Stones had to be removed so the land could be worked. These stones were gathered into heaps and also served for the construction of walls around agricultural plots. The land that developed on the Dalawa basalt is suitable for raising olives, and most of the olive orchards in the region were planted here. The areas that were not cultivates in this unit are covered with forest-park, in which the space between the trees – Mt. Tabor oak and terebinth – is relatively great. In the upper part of the region are remnants of a forest and of extensive pasturelands.

2.2.12 The Central Plateau – This area declines from 750 m above sea level in the east to c. 400 m above sea level in the west. It ends in the west at the top of a steep cliff. The streams here flow year-round in shallow channels. In the western part of the plateau they descend in waterfalls into steep canyons, which impede movement from north to south.

The area is mainly covered with rocky Dalawa basalt but there are also a few narrow flows of Muweisse basalt, on which arable soil developed. The ancient cover basalt was exposed in the western part of the central plateau.

Precipitation ranges from 700 mm a year in the east to 500 mm in the west. There are remnants of a forest in the area as well as pasturelands.

2.2.13 The Beteiḥa Streams – West of the central plateau a steep slope descends from 500 m above sea level to the Beteiḥa (Bethsaida) valley, at 130 m below sea level, north of the Sea of Galilee. The slope consists mostly of cover basalt.

In addition to Naḥal Meshoshim and Naḥal Yahûdiyye, the Daliyyot and Sfamnun streams also flow through the Beteiḥa Valley. Naḥal Batra, which flows into Naḥal Daliyyot, this unit’s main stream, flows along the Sheikh ‘Ali Fault and divides the Beteiḥa streams from the Meshoshim and Yahûdiyye drainage basin.

Naḥal Daliyyot dug itself beneath the basalt layers and exposed limestone of the Gesher Formation; continental sedimentary rock of the Herod Formation and chalk of the Maresha Formation. As opposed to the basalt, the sedimentary rocks eroded rapidly, creating a valley about 2 km wide. The stream dug deeply, in a series of waterfalls. In the eastern part its slopes are steep and almost unsuitable for habitation except for the Gamla spur and Ḥorbat Daliya. In the western part of the stream moderate terraces were created on which settlements were built.

Naḥal Sfamnun flows parallel to and south of Naḥal Daliyyot. All the streams drain into the Beteiḥa (Bethsaida) Valley. The areas between the streams and the moderate terraces are covered with forest-park consisting of Mount Tabor oak and terebinth.

2.2.14 the Beteiḥa (Bethsaida) Valley – six streams drain into this valley: the Jordan, Meshoshim, Yahûdiyye, Batra, Daliyyot and Sfamnun. The large quantity of alluvium brought by the streams has gradually filled the northeastern Sea of Galilee and created a valley approximately 12 sq km in area.

The valley is 130–200 m below sea level and its climate is hot. In addition to herbaceous and riparian vegetation, mainly Christ’s thorn jujube grows there. The steams cross the valley and near the Sea of Galilee beach are a number of lagoons and swamps.

2.2.15 Naḥal Samak and Naḥal Qanaf – Two streams that descend from the east, from 360 m above sea level, flowing into the Sea of Galilee at 200 m below sea level. Naḥal Samak creates a valley 4 km wide and 9 km long into which Naḥal Samak flows from the north and Naḥal el-‘Āl from the south. This fertile valley was settled in all periods.

The two streams dug deeply into the basalt layers and exposed thick layers of Maresha chalk and continental sedimentary rock of the Herod Formation. The rock is soft and erodes easily; consequently creating broad, deep valleys surrounded by slopes whose northern parts are cliff-like and covered with basalt and whose southern parts, covered with sedimentary rock, are more moderate. There is good, arable land at the bottom of these valleys. Small streams emerge on the seam between the basalt and the sedimentary rock, which provided water to settlements.

The climate is moderate in the upper part of the landscape unit and hot in the lower part. Roads ascending to the plateau pass through this unit.

2.2.16 The Sea of Galilee Cliffs – This series of cliffs and steep slopes, 300–400 m high, were created as a result of the Jordan Valley fault. Under the cover basalt, layers of a variety of sedimentary rock are exposed, of the Herod, Fiq and Sussita formations. These created steep slopes and the settlements in this unit are usually concentrated on the lower part of the slopes.

The streams along the slopes are short and have small drainage basins. An exception to this is Naḥal Sussita, which begins under the community of Afiq. The eastern part of the stream cuts into the continental sedimentary rock of the Herod Formation and creates a fertile valley. In the center is crosses a fault like between Maresha chalk and limestone of the Sussita Formation, where a short portion of the stream is a narrow, steep channel. Farther on, parallel to Sussita’s northern slope, the stream widens and has areas suitable for settlement and agriculture.

In the northern part of the unit, north of Kursi, and in the southern part, in the southwestern corner of the Golan, the slopes descend in a series of terraces that made settlement possible and a road to be built up to the Golan.

2.2.17 – The Southern Plateau – a flat area that descends from 450 m above sea level in the north to 330 m above sea level in the south. The plateau is bounded on the east by the deep valleys of Naḥal Ruqqad and Naḥal Meyṣar; and in the west, by Naḥal Samak and Naḥal ‘Ein Gev and by the slopes descending to the Sea of Galilee. On the south the plateau ends with the steep slope descending toward the Yarmuk River.

2.2.18 Naḥal Ruqqad – This stream begins at the foot of Mount Hermon in the north, where it flows through a shallow, almost imperceptible channel, while its southern portion flows through a valley 200 m deep and 2–3 km wide. Continental sedimentary rock of the Herod Formation is exposed on the slopes; Susita limestone and chalk from the ‘Adulam Group. The stream bed bears remnants of the Ruqqad basalt flow, created from lava that flowed through the steam bed.

The slopes of the valley are quite steep but it has moderately sloped terraces and areas suitable for agriculture.

2.2.19 – Naḥal Meyṣar ¬– this stream descends from the southern plateau to the Yarmuk in a southeasterly direction. The stream digs its way under layers of cover basalt and exposes rocks of the Herod Formation and chalk of the Maresha Formation and the ‘Adulam Group. The rock is soft and erodes easily, consequently creating a valley 6 km long and 4 km wide, with moderate areas that lend themselves agriculture. Small springs emerge from the seam between the basalt and the sedimentary rock. The climate is moderate in the upper part and hotter in the lower part. The combination of agricultural soil, water and a comfortable climate is suitable for settlement and the valley was settlement throughout almost all periods.

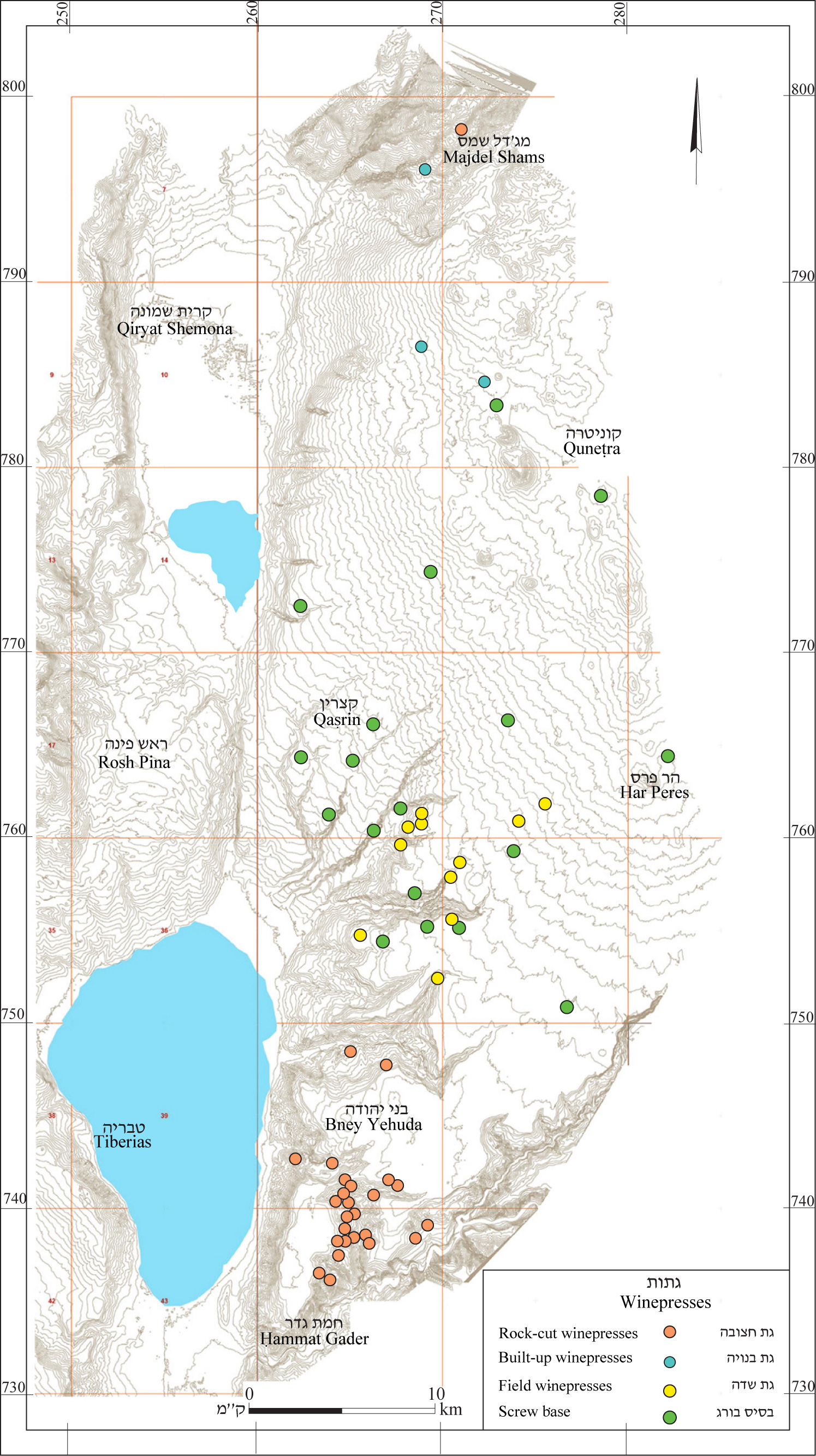

The chalk rock is suitable for quarrying and therefore this landscape unit contains many winepresses, caves and rock-cut tombs.

2.2.20 The Yarmuk River – A long stream that cuts into the border between Syria and Jordan. Only the lower part of the stream is within the boundaries of the State of israel, after the Ruqqad flows into it. In this portion of the stream it creates a deep, wide valley, which, like the Ruqqad, cuts into the cover basalt and the rocks of the Herod, Sussita and Maresha formations and chalk of the ‘Adulam Group. In the streambed are remnants of two basalt flows. The more ancient one is Yarmuk basalt; above it is Ruqqad basalt. As it flows, the Yarmuk creates a small valley in which the hot springs of Ḥammat Gader and el-Mukheiba emerge. Opposite Ḥammat Gader the stream flows through a deep canyon until it emerges in the Jordan Valley.

3. Settlement Potential in the Golan

“According to the nature of the soil, the Jaulan may be divided into two districts: (1) stony in the northern and middle part, (2) smooth in the south and more cultivated part” (Schumacher 1888:11). In this single sentence, Gottleib Schumacher expressed the great difference in settlement potential between the two parts of the Golan.

3.1 The Northern and Central Golan

This settlement potential of this area is relatively low, mainly limited by a lack of soil and water. The lack of good soil for agriculture is common to most of the landscape units in this area; most of it is suitable for grazing only. Areas with soil are limited and a major investment is required to rid the land of rocks and upgrade it.

The lack of water is also a limiting factor. The area in general gets a great deal of precipitation, and in the northeastern part precipitation is very great, and is therefore suitable for rain-fed agriculture. However, in fact, the amount of water available to farmers is much smaller. The great fluctuation in precipitation from one year to the next and its fluctuations over the season often cause major damage to farmers. A few drought years in a row can lead to the abandonment of the region.

Despite the major precipitation, the area lacks major water sources. This is because the basalt flows create shallow water tables where the emerging springs are small and usually run dry in the summer. The basalt rocks are also hard and difficult to quarry and are therefore unsuitable for digging cisterns. That is the reason that cisterns and wells are rare in this area. Most of them are located in the villages of the Circassians, who came to the Golan in the 1870s from an entirely different type of region.

A good deal of the area once bore thick forests, which had to be cut down and to take advantage of the soil. This was only worthwhile in areas where the forest covered good, arable soil. The marginal areas remained forested or were deforested in times when a population boom required additional agricultural areas.

The major advantage of this area, however, is its excellent pasturelands. The northern and central Golan are considered the richest grazing area in all of southern Syria. As noted above, most of the area is not suitable for agriculture and therefore extensive portions remained uncultivated. Moreover, the area’s large quantities of precipitation assured good pasturage year-round.

The height differences between the western and eastern parts of this region were also advantageous to herders. Vegetation grew at different rates, which allowed for a longer grazing season. When pasture ran out in the lower part of the region – in late spring or early summer, the shepherds could lead the flocks up to the higher parts, where extensive pasturage remained. The small springs, while not abundant enough for farmers, were useful to shepherds for watering their cattle, sheep and goats.

It is therefore not surprising that the region attracted nomadic tribes from the Bashan and the Hauran. Nomads in such numbers constituted a continual threat to farmers and during periods when the central government was weak, this state of affairs could lead to the abandonment of permanent settlement in the area.

3.2 The Southern Golan

The plateau in this area is narrow and bears ancient eroded cover basalt that created deep soil with few rocks. This area is suitable for field crops and was cultivated extensively for long periods. Most of the settlements were built along the edges of the plateau, freeing much of the area for cultivation. The plateau is bounded on the east and the west by broad, arable stream valleys and small springs that made irrigated farming possible.

The climate in the southern Golan is more moderate than in the north. Since this area is lower than the northern Golan, it suffers less from frost. The amount of precipitation is smaller than in the north but it is sufficient to ensure the growth of winter wheat each year. The combination of good soil and a moderate climate led to continuous settlement throughout almost all periods. The stream valleys became preferred areas of settlement. They were very densely settled for much of their history and in a number of periods, settlement concentrated only there. The settlements in the southern plateau, which were fewer but larger, were farming settlements whose inhabitants lived permanently on their land.

Pastureland on the southern plateau is meager compared to the center and north and so throughout all periods it was less attractive to nomadic tribes, although they were present to some extent.

4. History of Settlement according to Archaeological Findings

A detailed description of the types of settlements in the different periods, in the context of geographical location, is presented in the introduction to each individual survey. This chapter will present the general picture of settlement in the Golan and the Hermon. Discussion is based on the analysis of the surveys of the central and southern Golan that have been published on this website. The description of settlement in the northern Golan is based on publication of the Northern Golan Survey (Hartal 1989).

For the reader’s convenience I have minimized notes directing to earlier studies. All the documents and publications, including references to additional sources, are included in the Bibliography.

4.1 The Chalcolithic Period

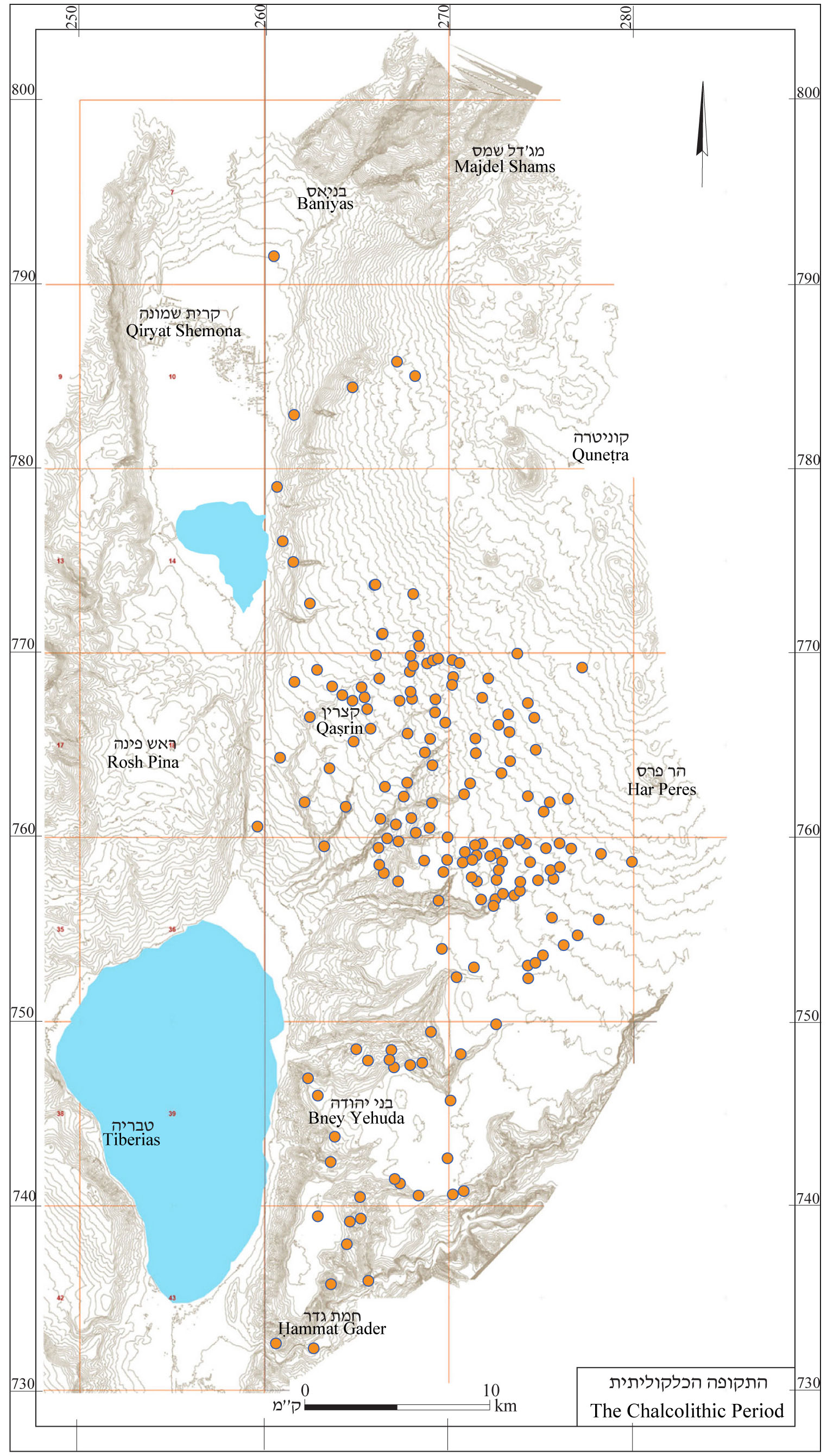

4.1.1 Central Golan – This region saw a major wave of settlement in this period (see map 2). One hundred and eighty sites were surveyed, 135 of them in the central Golan, where a Chalcolithic culture was revealed that had been previously unknown to research. There were small, unwalled settlements in this area, most of which were built in streambeds, which in this area were shallow. Such a streambed is known locally as a masil. The Chalcolithic culture of the Golan has been extensively studied by C. Epstein, who surveyed dozens of site and excavated many of them (Epstein 1998).

The dwellings in these settlements are uniform. They are of the broadroom type and include two rooms, one larger than the other; the latter, usually in the west, apparently served for storage. Most are built as chains of houses, parallel to each other. In a number of cases walls were found that connected the chains of houses and created a sort of courtyard.

In many houses small basalt pillars were found, the top of which was convex, and bore a relief of a nose, eyes and sometimes a male goat’s horns and beard. These reliefs have been interpreted as house gods.

The uniformity of the houses attests to an egalitarian society with no wealthier class. It seems that the inhabitants were farmers who worked small plots of land in the masils (see above), which have water even in the summer months. Epstein believed that this was the period in which the olive was domesticated. The inhabitants also raised sheep and goats and possibly cattle as well. The settlements were mainly established on virgin ground. Their inhabitants came from outside the area and just as they arrived, they disappeared. Most of the settlements from this period were abandoned and never rebuilt. Their remnants remained exposed on the surface. There was practically no cultural continuity between the Chalcolithic period and the Early Bronze Age.

4.1.2 In the Northern Golan – Thirteen sites were found in the northern Golan from the Chalcolithic period. Findings from this period are very meager and were discovered during earthworks that revealed potsherds that could not be seen on the surface. Other sites may have been covered up and disappeared. The sherds found in the northern Golan are similar to those in the center; they apparently belong to the same period. However, the paucity of finds makes it difficult to determine this with certainty.

4.1.3 In the Southern Golan – Here, the Chalcolithic culture was different. There are fewer sites in this area than in the central Golan – only 32 – and they were widely spaced. The pottery resembles that of the Jordan Valley, although pottery was also found that is typical to the central Golan. As opposed to the central Golan, the sites in the southern Golan were not extensively researched and information about them is limited.

4.2 The Early Bronze Age

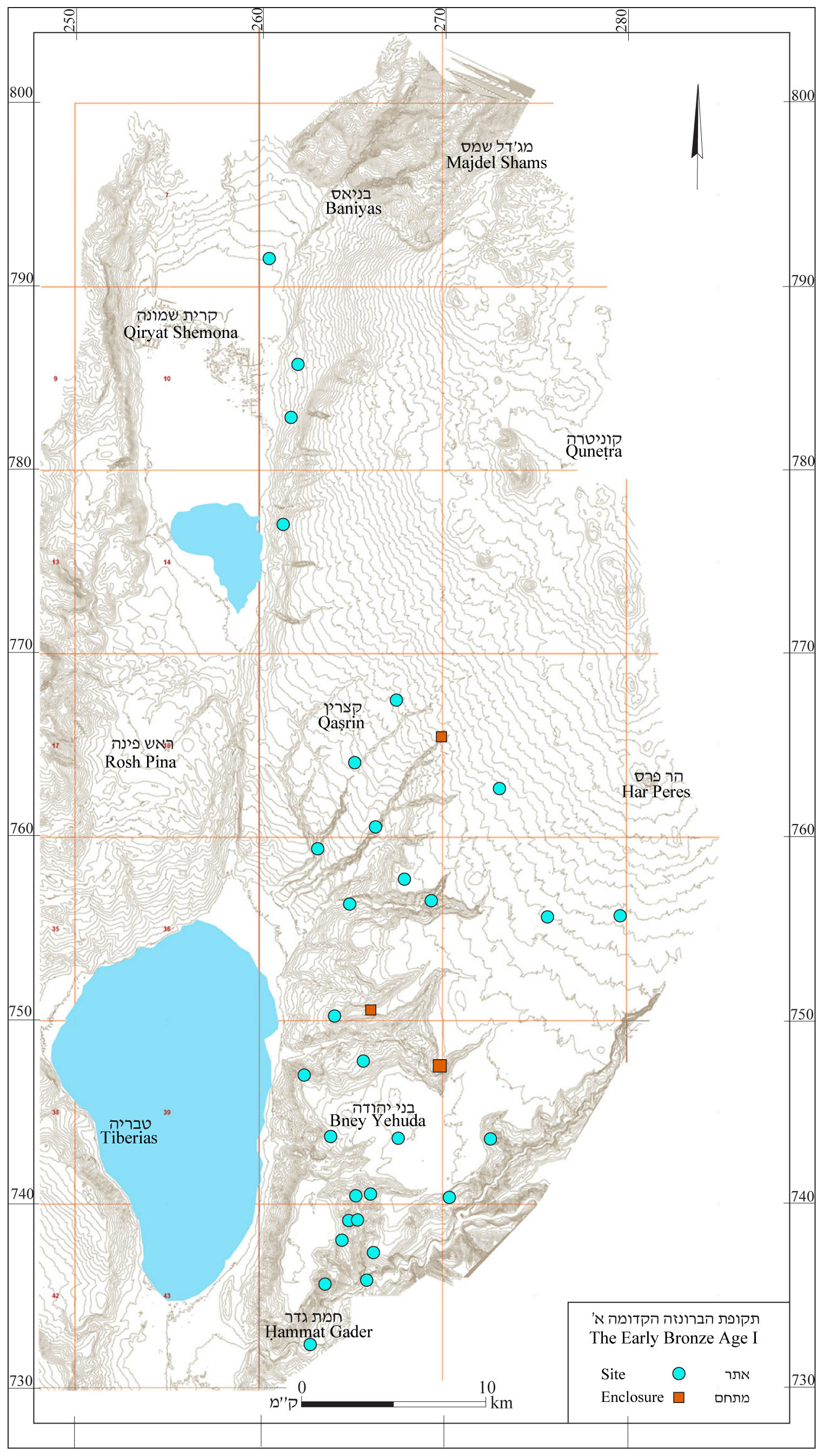

4.2.1 In the Early Bronze Age I – Settlement in the Golan was renewed at this time (see map 3) and site distribution is completely different than during the Chalcolithic period. This is testimony to the lack of settlement continuity between the two periods.

In the southern Golan 17 sites were found from the EB I, apparently all villages built in streambeds. In the central Golan, 15 widely spaced sites were found. Only three of these were found on the central plateau; the rest were in the streambeds. In the northern Golan, four sites from this period were found, all on the slopes facing the Hula Valley.

4.2.2 In the Early Bronze Age II–III – The distribution of settlements changed at this time (see map 4). Only 12 settlements from the EB I continued in existence.

There were 24 settlements in the southern Golan, 43 in the center and 41 in the north. Most of the settlements were apparently unwalled villages built on level areas and in the stream valleys. The EB II–III is the only period in the history of the Golan in which there was an apparently uniform culture throughout the Golan.

4.2.3 The enclosures – Among the dozens of sties from the Early Bronze Age discovered in the Golan, a number of sites are prominent that were not previously known. These sites have been dubbed “enclosures” (enclosure = Mitḥam in Hebrew)

Three of the sites, Mitḥam Iṣḥaqi (Qaṣrin Survey, site no. 60), el-Bardawil (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 43) and Leviah (Ma‘ale Gamla Survey, site no. 94). They are located on spurs surrounded on three sides by cliffs and steep slopes, whereas the fourth side, which could be easily accessed, was enclosed with a broad wall, built of large fieldstones. At Gamla (Ma‘ale Gamla Survey, site no. 42), which is situated on a steep spur, excavations revealed remains of structures from the Early Bronze Age. This site may also have been a “mitḥam”; however, no remains of a wall enclosing the spur have yet been found. Three sites – esh-Sha‘abaniyye (Rujem el-Hiri Survey, site no. 44), ‘Ayit Enclosure (Qeshet Survey, site no. 62) and Mitḥam ‘Ani‘am (Qaṣrin Survey, site no. 81) were surrounded by similarly built walls. In two sites, Ḥorvat Zawitan (Ma‘ale Gamla Survey, site no. 2), and ed-Dura (Qaṣrin Survey, site no. 41) a moat was dug across the spur as an alternative to a protective wall.

All these enclosures were found in the central Golan, east of the Sea of Galilee, at an altitude of 220–550 m above sea level. In the first surveys, no remains of structures were found and so these remains were called, as noted, “enclosures.” Initially it was proposed that they had been built as protection for nomads and their flocks in wartime. Later surveys uncovered wall traces revealing the presence of a settlement at these sites.

In excavations at Mitḥam Leviah, the largest of these sites, remains of structures were found within the walls from all periods of the Early Bronze Age (Paz 2003), Based on these findings, all the enclosures are now identified as fortified cities; however, this identification raises a number of questions.

The economic potential of the central Golan is quite limited. The land in the area is rocky and unsuitable for agriculture. The main livelihood was the raising of cattle and sheep and goats, which enjoyed the rich pastureland. This area could not economically support cities and indeed, until Second Temple times when olive cultivation expanded there were no cities in this area.

If all of these enclosures contained cities, it is unclear what their economic basis was. Moreover, four of the sites (Gamla, ‘Ayiṭ, Ani‘am and Mitḥam Iṣḥaqi) are only 1.5–2 km apart, which limits their economic options even more.

It is also important to note that these enclosures differed in their plan and location from the known Early Bronze Age cities in this country. Such enclosures were found in marginal areas of the Lower Galilee and Samaria and in all of them there seemed to be no proportion between the walls surrounding the enclosure and the meager, if any, remains within them.

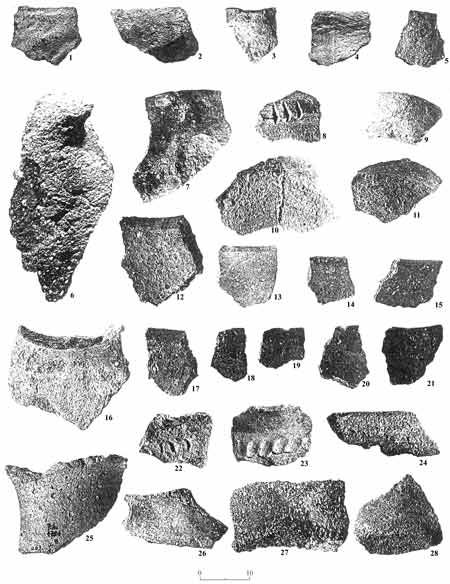

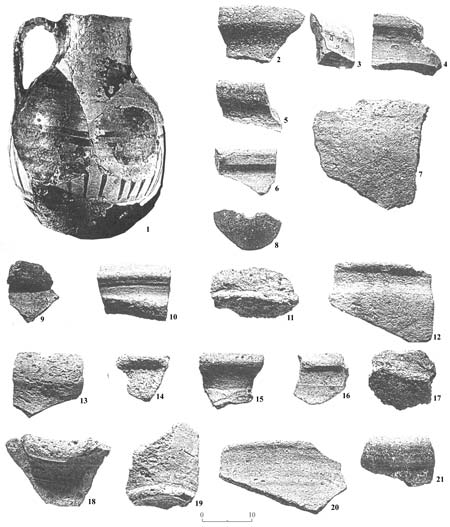

4.2.4 Pottery Industry – At the foot of Mount Hermon, particularly around ‘Ein Quniyye, evidence was found of pottery manufacture typical of this period – metallic pottery. These vessels made of well-fired clay and were used in the northern and central parts of the country. At the site of ‘Ein el-Raḥman (Dan Survey) an accumulation of jar sherds was discovered, some of which were decorated by cylinder stamps. The sherds were found in a trench created during road building. Basalt potters’ wheels were found on the surface.

At the end of this period all the settlements in the Golan were abandoned.

4.3 The Intermediate Bronze Age

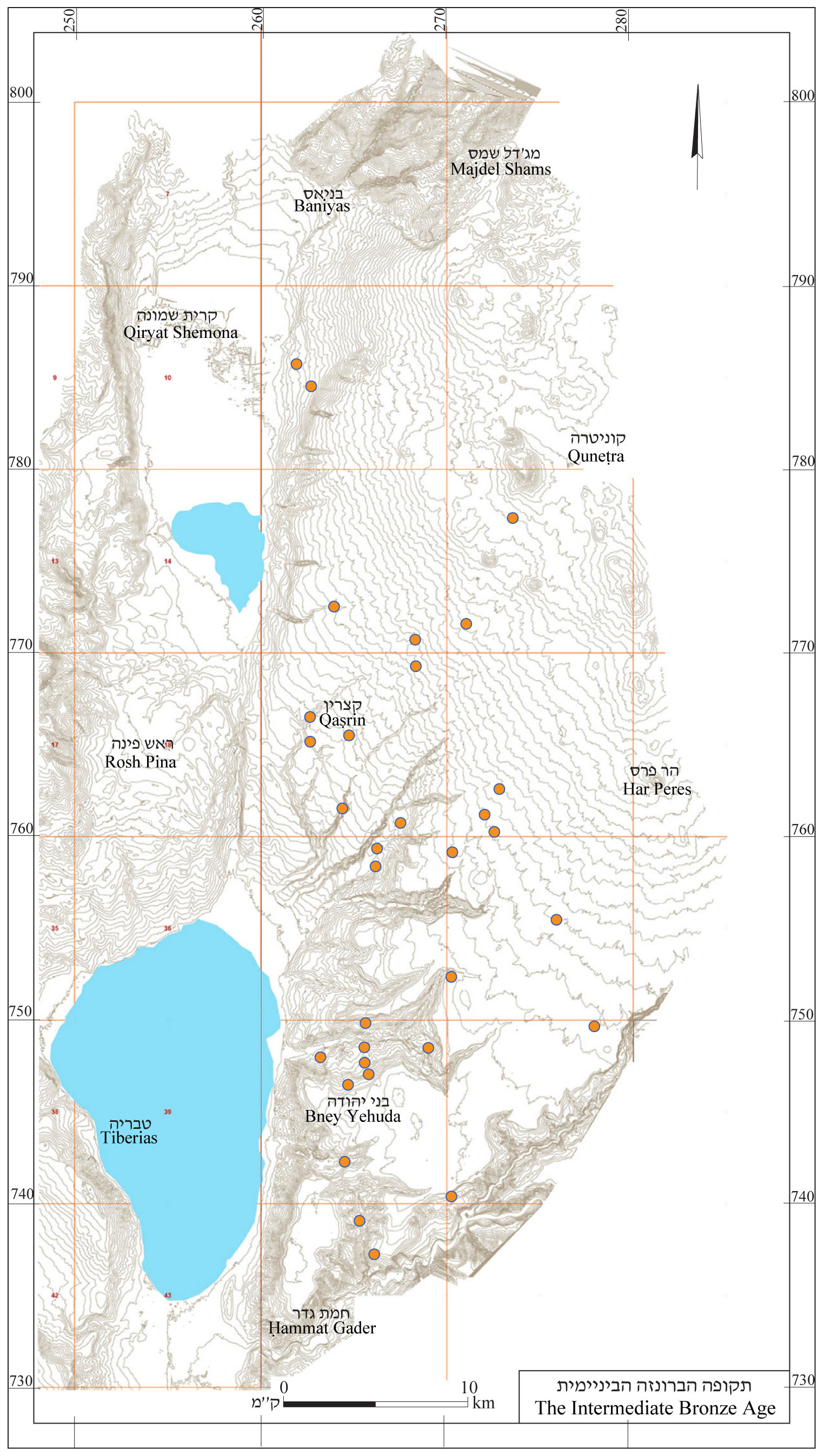

Some 30 sites were found from the Intermediate Bronze Age (see map 5). Most of these revealed sherds only. The density of settlement in this period was very low. Twelve sites each were found in the central and the southern Golan. In the north, six sites were found.

As in other periods, the area filled with nomads or semi-nomads, who took advantage of the abundant pasturelands. Their presence was signaled by the thousands of dolmens scattered across the Golan (see below, Chapter 5).

Numerous shaft tombs were found at 14 sites, in the limestone areas of the southeastern Golan – nine in the Ḥammat Gader Survey area and four in the ‘Ein Gev Survey area. These tombs were not excavated and therefore their dating is uncertain.

Shaft tombs were in extensive use during the Intermediate Bronze Age. The Intermediate Bronze Age is typified by a large variety of tombs, usually individual tombs. These characteristics are typical both to dolmens and shaft tombs, although these two types of burials are very different in their form and construction techniques.

4.4 The Middle Bronze Age II

4.4.1 Before discussing the finds from the period, its name must be clarified. The Middle Bronze Age was once divided into two sub-periods – “Middle Bronze Age I” and “Middle Bronze Age II.” Since the Middle Bronze Age I was very different in its characteristics from the Early Bronze Age that preceded it and the Middle Bronze Age that came after it, its name was changed to the “Intermediate Bronze Age.”

Following this name change, the next period was called the Middle Bronze Age II without there being a Middle Bronze Age I (see the table of chronological periods in the The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Stern 1993). To correct this situation, in recent years the name of the first part of the Middle Bronze Age II was changed to the Middle Bronze Age I, and the name “Middle Bronze Age II” was taken as the name of the second part of that period. The name change is logical; however, it can cause confusion in terms of earlier publications and therefore we continue to use the former terminology.

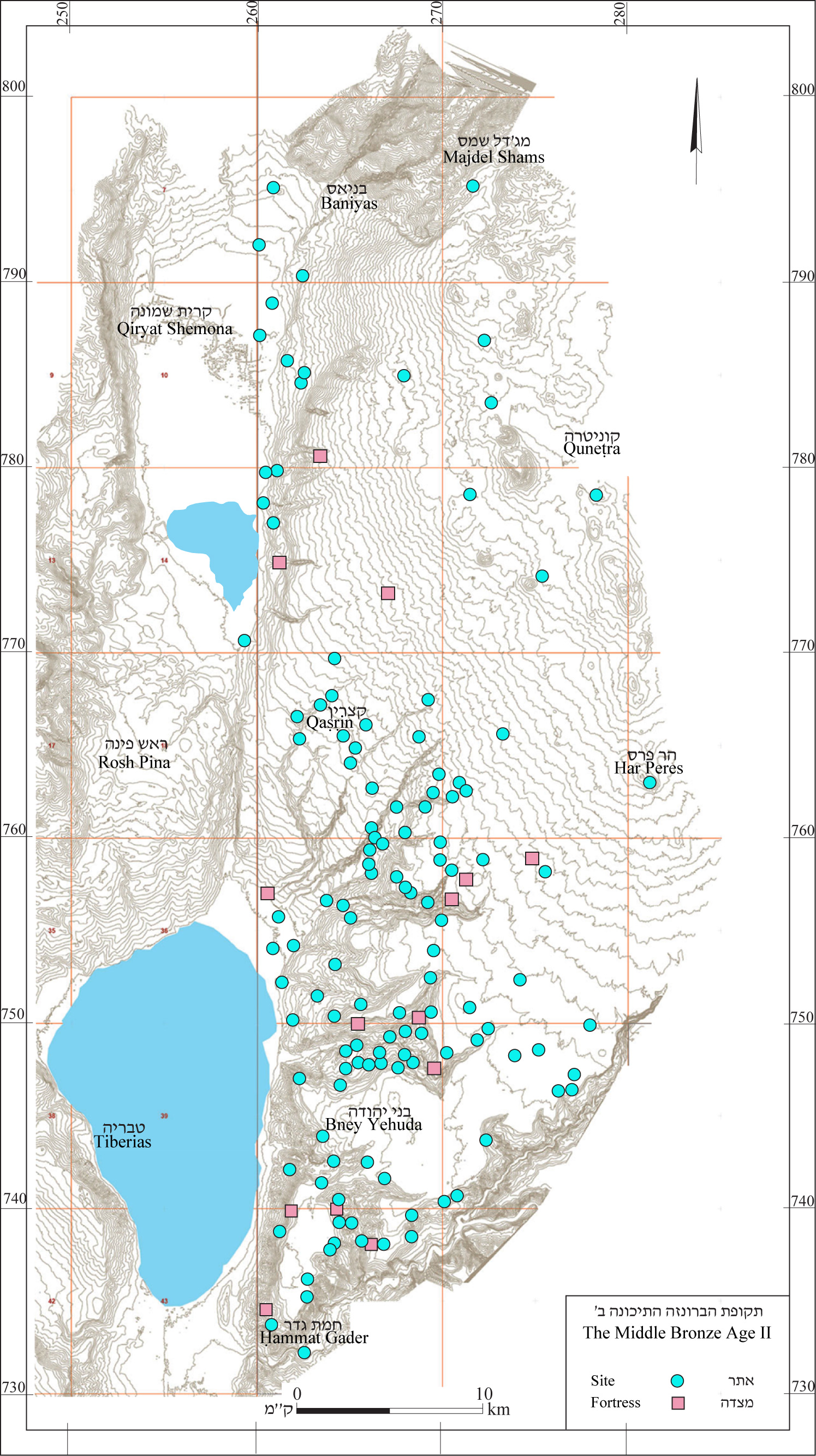

4.4.2 During the Middle Bronze Age II, settlement was renewed in the Golan. Remains from this period were found in 138 sites (see map 6). Sixty-four sites were found in the southern Golan, 58 in the central Golan and 16 in the northern Golan.

Most of the settlements are concentrated in three dense settlement clusters in the stream valleys. In the Yarmuk and Naḥal Meẓar that flows into it, 22 sites from this period were identified. On the terrace below Mevo Ḥamma a concentration of five sites were found in an area of 1 sq km. In the Naḥal Samak basin, 25 sites were found and in the Beteiḥa basin, 37 sites were found from this period. Additional sites are scattered across the plateaus.

The finds from this period have still not been thoroughly studied, but it seems that these sites represent cities, villages and fortresses. The distribution of the sites in dense clusters may perhaps attest to different political unites in the southern Golan at this time.

4.5 The Late Bronze Age

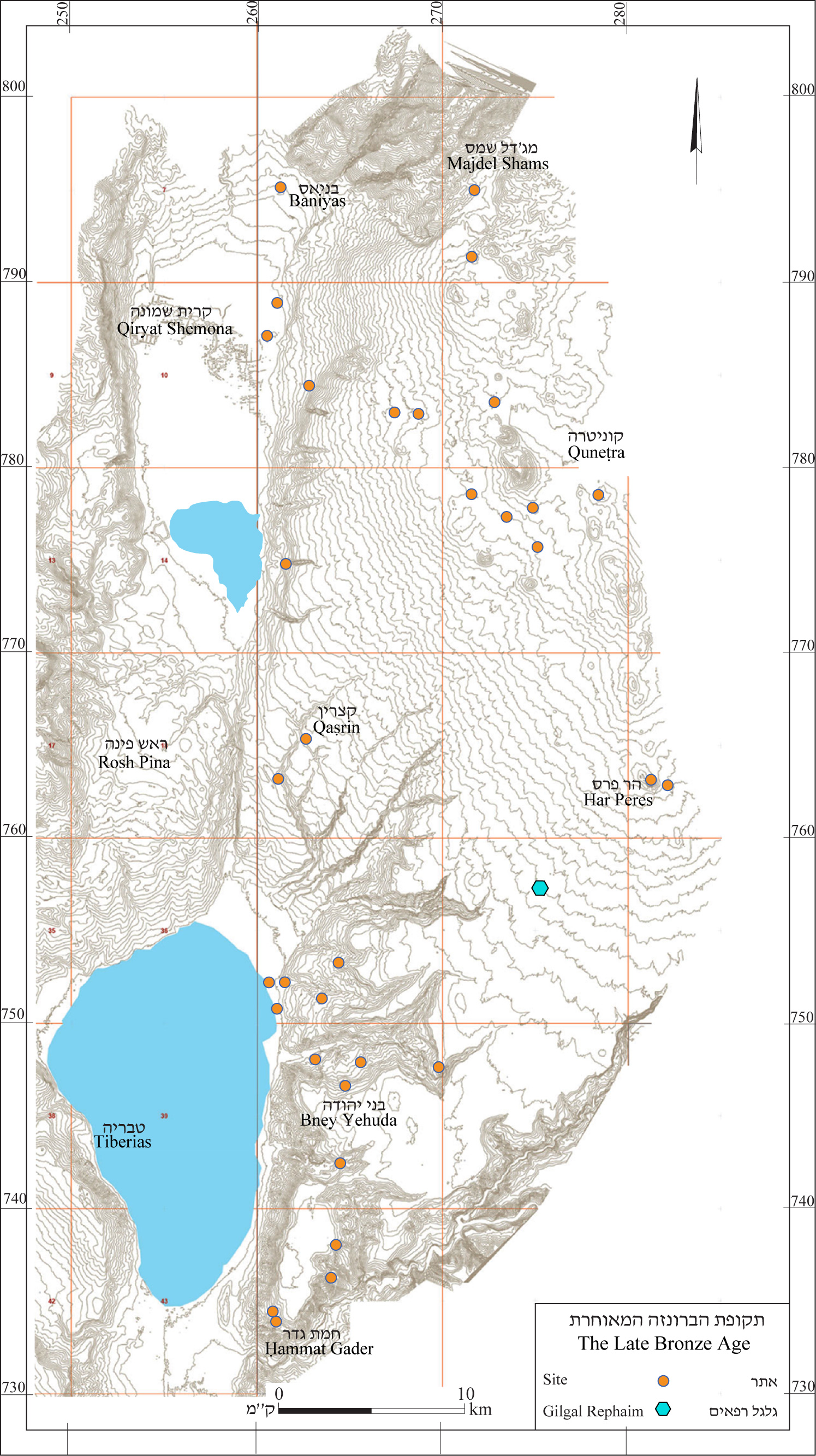

4.5.1 Settlement continued during the Late Bronze Age in the stream valleys, but the numbers dwindled greatly. Only 14 sites were found in the southern Golan, all in the valleys of Naḥal ‘Ein Gev, Naḥal Samak and Naḥal Kanaf (see map 7). At Tel Hadar (Ma‘ale Gamla Survey, site no. 89) on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, an administrative center was founded. The site was surrounded by a wall or two walls. In excavations at the site, two floors were found, bearing tools and abutting the wall. On the northeastern side part of a well-preserved round tower was found. The settlement was destroyed around 1500 BCE (Kochavi 1996:190). Remains of four sites were found in the Naḥal Samak basin, one of which was on the Kinnar Beach (Ma‘ale Gamla Survey, site no. 73), on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, and three sites were found at a point with a controlling view of the stream valley. Few sites were found on the southern and central plateau. Two were found in the Har Peres Survey area, and one site each in the Rujem el-Hiri and Qaṣrin Survey areas. No sites were found from this period in the Nov or Qeshet survey areas. In the northern Golan, 15 sites were found from the Late Bronze Age, some of which featured only dolmens. Among the settlements of the southern and northern Golan was an area in the central Golan that had practically no settlements. It is possible that the settlements in the southern Golan belonged to the kingdom of Geshur and those of the northern Golan to the kingdom of Ma‘acah (see below, 9.2).

4.5.2 The steep decline in the number of settlements left large areas without settlements. As in other periods, these areas seem to have been in the hands of nomads or semi-monads. While these people left no remains of buildings, they did leave their imprint on the area.

Between Rujem el-Hiri in the south and ‘Ein Zivan in the north are large stone heaps covering dolmens. These dolmens are built of relatively small stones arranged in rows slanting inward and forming a kind of false dome, at the top of which a large stone slab was placed. In two of these heaps, sherds were found from the Late Bronze Age. These heaps are usually surrounded by smaller dolmens built in the usual manner. It seems that these were dolmen fields, built in the Late Bronze Age, and that they served as burials for nomads (see below, 5.1).

4.5.3 The tomb in the middle of Rujem el-Hiri (Hebrew: Galgal Refaim) is built in a fashion similar to the heaps described above, and excavations revealed finds from the Late Bronze Age. There is no doubt that this site was in use at that time and therefore it is presented here. However, scholars are divided on the question of whether this was secondary use of an ancient structure or whether the structure was first built in the Late Bronze Age.

Although no finds were discovered that dated it to a period other than the Late Bronze Age, a number of dates have been proposed. Michael Freikman (pers. comm.) suggested that it be dated to the Chalcolithic period. Mataniya Zohar, Moshe Kochavi and Yonatan Mizrachi dated (below) the construction of the curving walls to the Early Bronze Age. Zohar (1992) also believed that there was a monument of some kind in the center of the structure. Kochavi posited that the central heap was built in the Early Bronze Age and that the finds within it attest to secondary use in the Late Bronze Age (Kochavi 1993). Mizrachi proposed that the heap was built in the Late Bronze Age in the center of the circles, which themselves were built in the Early Bronze Age (Mizrachi 1992). Moshe Hartal (1991) suggested that the entire complex was built in the Late Bronze Age (See below, 5.1.1).

The function of the structure is also unclear. Yehoshua Yitzhaki (1993) suggested that it served as an astronomical observatory. According to Aveni and Mizrachi its purpose was to forecast the first rain (Aveni and Mizrachi 1998). Hartal (1999) proposed that the site served as a cult center for a pastoral population.

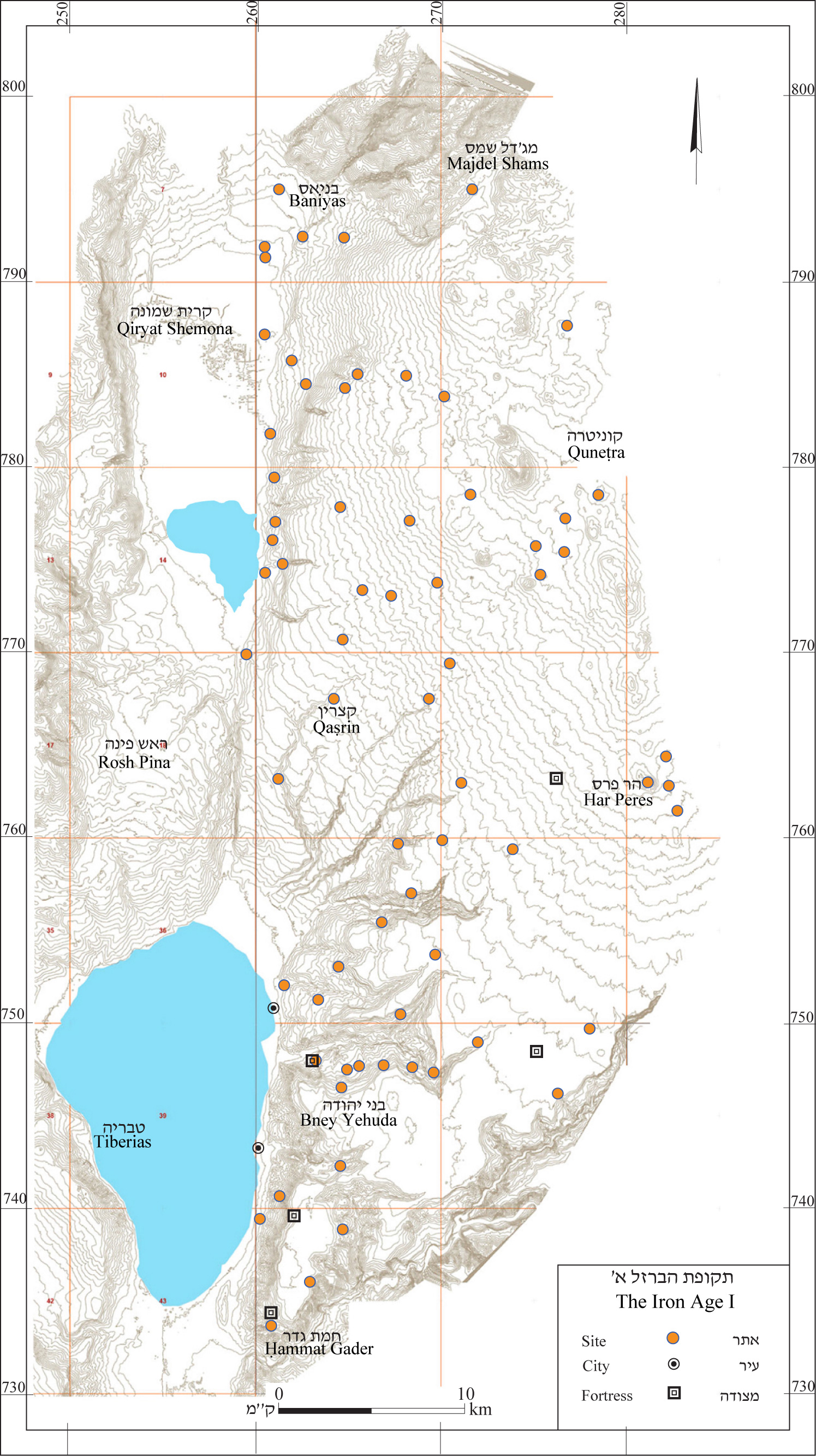

4.6 Iron Age I

During the Iron Age I the number of settlements increased in the Golan (see map 8). In the southern Golan, 20 sites from this period were found, in the center, 24 and in the north, 31 sites. Most of the sites were found in areas not settled in the Late Bronze Age and most were situated in stream valleys.

Near the shore of the Sea of Galilee were two administrative centers, Tel Hadar (Ma‘ale Gamla Survey, site no. 89). At Tel Hadar settlement was renewed in the twelfth century BCE. In the eleventh century, the settlement expanded and served as a walled administrative center. It contained large storehouses in which taxes were collected from surrounding settlements. It seems that this was one of the administrative centers of the Land of Geshur (see below, 9.2.1). The settlement with its storehouses was destroyed in the eleventh century BCE by a major conflagration (Kochavi 1996: 190–192). In the early tenth century BCE, the fortified city at Tel ‘Ein Gev was founded (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 68).

The densest cluster of settlements was in Naḥal Samak. Six sites were found there, which were apparently villages. A fortified settlement, at el-Khashash (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 15) protected the entrance to the stream valley from the direction of the Sea of Galilee. This period was the height of the development of this settlement.

There were only a few sites on the plateau at this time, some of which were apparently fortresses. Remains of fortresses from this time were found at Tel Abu Zeitun (Nov Survey, site no. 24) on the southern plateau while Meẓad Yonatan (Qeshet Survey, site no. 62) was on the central plateau. Sites were also few in the Meshoshim-Yahûdiyye basins as well as the central plateau. It seems that these areas were still under the control of nomads or semi-nomads and the fortresses were apparently intended to control them.

During this period on the northern Golan, small sites were established, apparently of nomadic settlements, perhaps of the Ma‘acah tribes (see below, 9.2.1). In Wadi Balua‘ (Shamir Survey) remains were found of a fortress. There may also have been fortresses at other sites on hills controlling the roads and near water sources. The sites – Ṣurman (Har Shifon Survey), Somaka (Shamir Survey) and Miṣpe Golani (Dan Survey) – suggest the possibility that there too, there were fortresses.

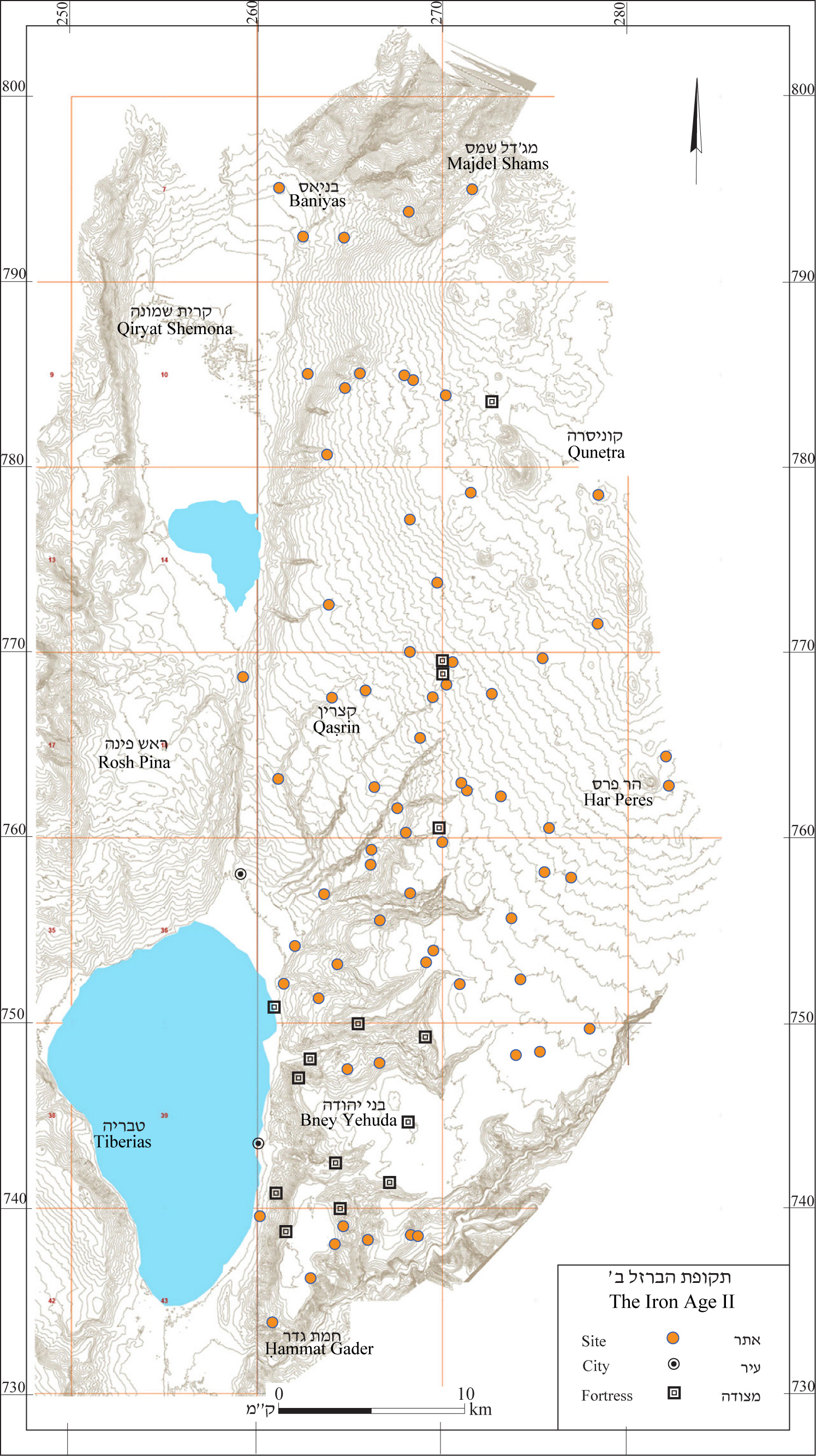

4.7 Iron Age II

During the Iron Age II the number of settlements grew. In the southern Golan the number increased from 20 to 39. In contrast, the northern Golan saw a sharp decrease in sites from 27 in the Iron Age I to 18 in the Iron Age II (see map 9). The reason for the decrease might have been the abandonment of small settlements that are typical of the beginning of the sedentary process, and consolidation into larger settlements.

In Naḥal Samak about half the Iron Age I settlements were abandoned and four new settlements were built, on hills with a controlling view of their surroundings and convenient to defend. Tel Sorag (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 89), as was the city at Tel ‘Ein Gev (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 68).

Sherds from the Iron Age II were also found at controlling points at the Ṣuqye Kawarot (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 111); at Rujem Fiq (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 66). At Maṣokey Onn Fortress (Ḥammat Gader Survey, site no. 2) and forts may also have been built at ‘Uyun Umm el-‘Azam (Ḥammat Gader Survey, site no. 27).

The change in settlement distribution reflects a change in the geopolitical situation at that time. During the Iron Age II the region was under the control of the Arameans and became the battleground between Israel and Aram (see below, 9.9.2). It was only natural for settlements to have been established in easily defensible locations and that fortresses were built as protection against invasion.

In the ninth century BCE settlement was renewed at Tel Hadar (Ma‘ale Gamla Survey, site no.89). Atop the ruins of public buildings a planned domestic quarter was built with streets, colonnaded structures and silos. During the last phases of the settlement in the eighth century BCE it served as a fishing a farming village and not as an administrative center. The settlement became more densely populated and the inner wall was done away with (see above, 4.5.1).

In Naḥal Meyṣar (Ḥammat Gader Survey), which was farther from the area of the battles, a number of smaller settlements were built, some of which continued settlements from the Iron Age I and others that were built during the Iron Age II.

New settlements were established in the central plateau (Rujem ae-Hiri and Qeshet surveys) and in the Meshoshim- Yahûdiyye basins (Qaṣrin Survey). These were apparently nomadic settlements. It seems that the process of sedentation, which began in the northern Golan during the Iron Age I, spread during the Iron Age II to the central Golan as well.

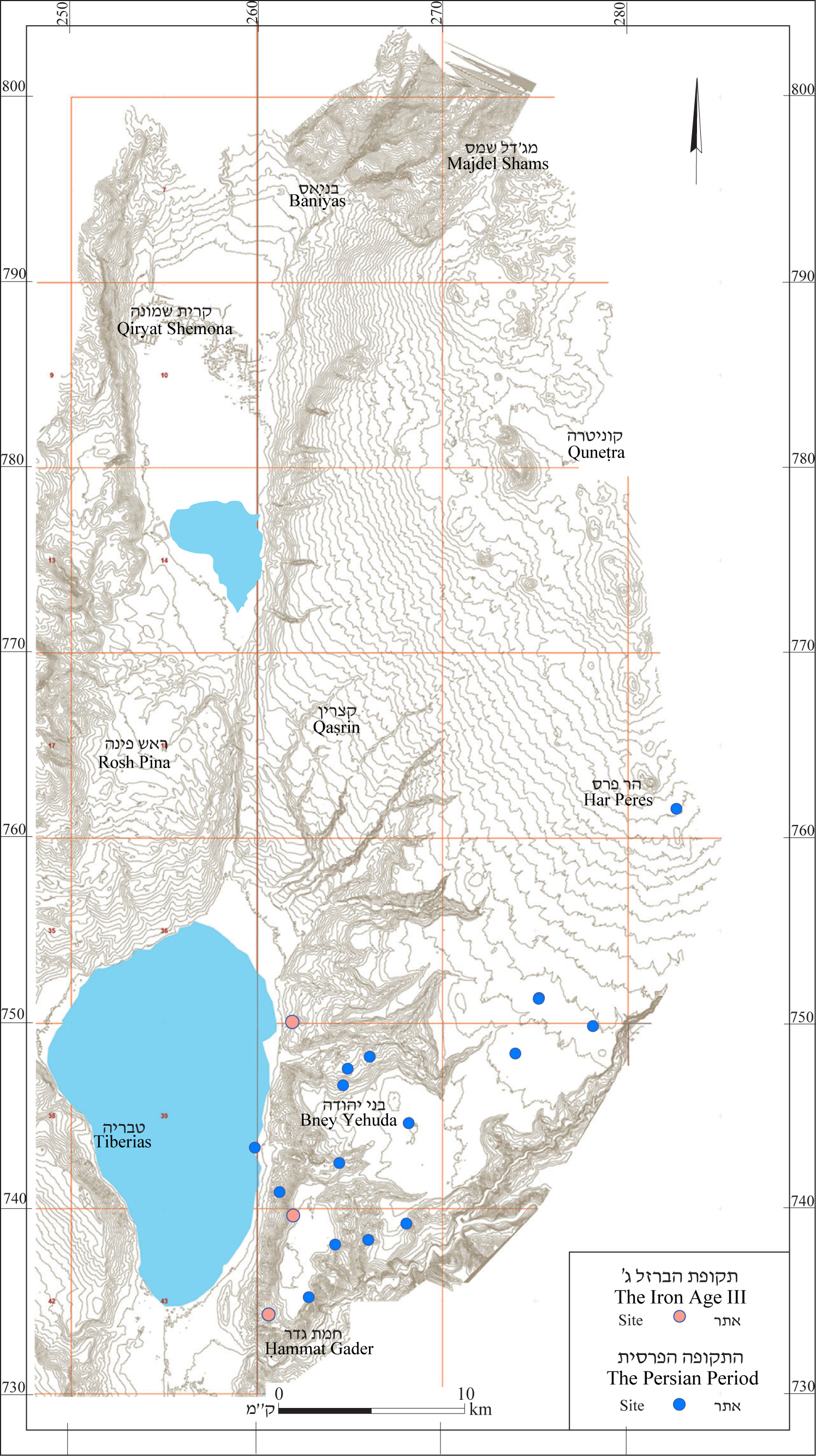

4.8 Iron Age III

The campaign of Tiglath-Pileser III against Israel in 732 BCE brought about the destruction of the settlements in the Golan. All the permanent settlements in the central and northern Golan were abandoned, leaving the area devoid of permanent habitations. The settlements in the southern Golan were also damaged and abandoned (see below 9.2.3)

Remains from the Iron Age III were found at only four sites (see Map 10). Three of these were built at controlling points in the area of the Ḥammat Gader Survey and one site was built in the area of the Ma‘ale Gamla Survey. With most of the Golan now devoid of permanent habitations, it seems that, as in other periods of settlement gap, the area was taken over by nomads and semi-nomads.

4.9 The Persian Period

In the northern and central Golan, the settlement gap persisted into the Persian period, however; in the southern Golan in this period settlement began again. Remains from the Persian period were found at 12 sites, most of which were in the southern Golan (see Map 10).

In the excavations of Tel ‘Ein Gev (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no.68), only pits were found from this period. At Tel Sorag (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 89) settlement was renewed and excavations revealed buildings and silos; the site may have been a village.

Sherds from the Persian period were also found at Ṣuqye Kawarot (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no.111) and in Naḥal Samak (‘Ein Gev Survey, site nos. 30 and 39). In Naḥal Meyṣar (Ḥammat Gader Survey 39, 56 and 67), in the Yarmuk Valley (Ḥammat Gader Survey, site no. 24) and on the southern plateau (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 66; Nov Survey, site nos. 14 and 23). Ḥorvat Boṭma (Har Peres Survey, site no. 2) is the northernmost site were remains from the Persian period were found.

4.10 The Hellenistic Period

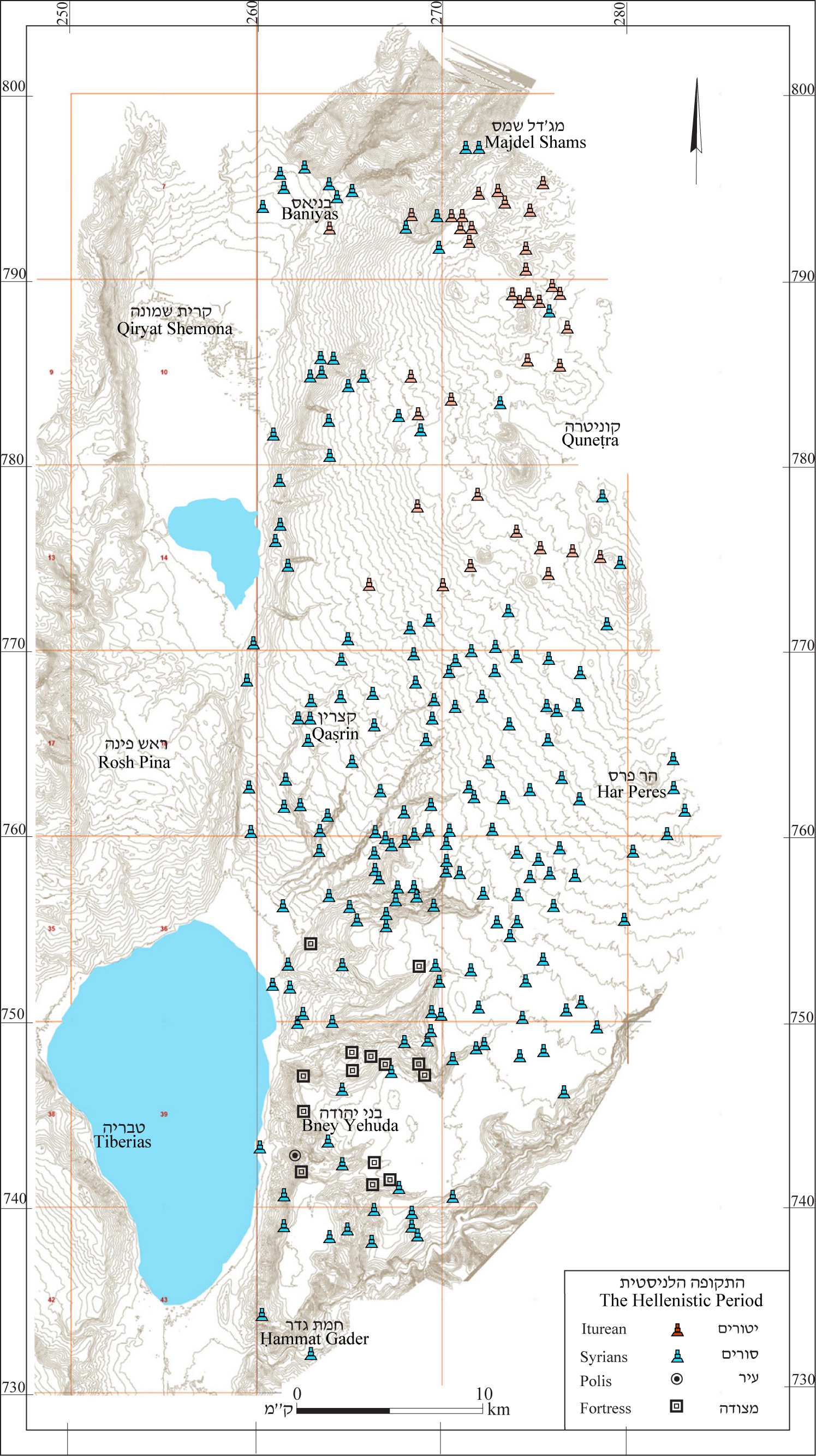

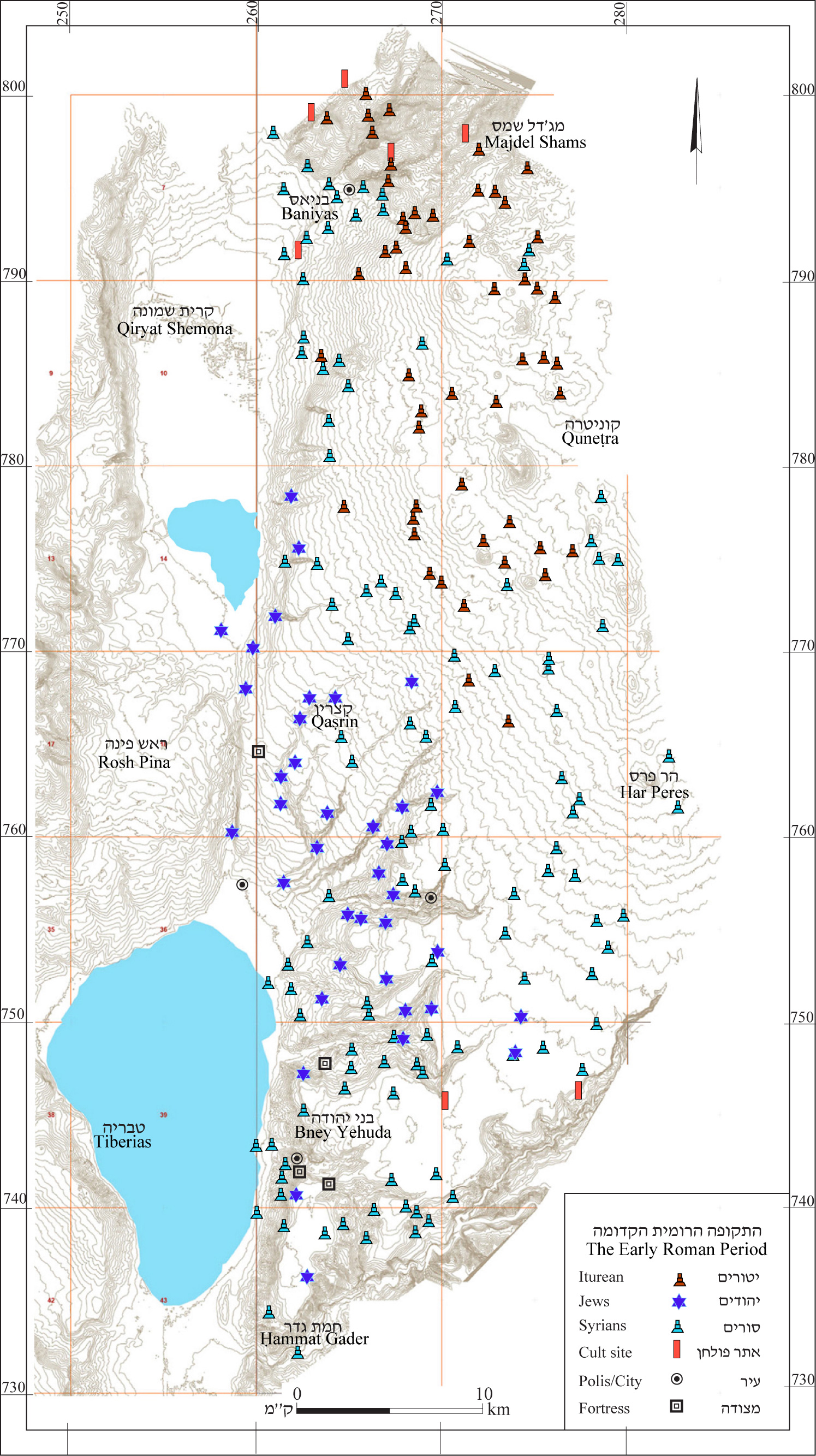

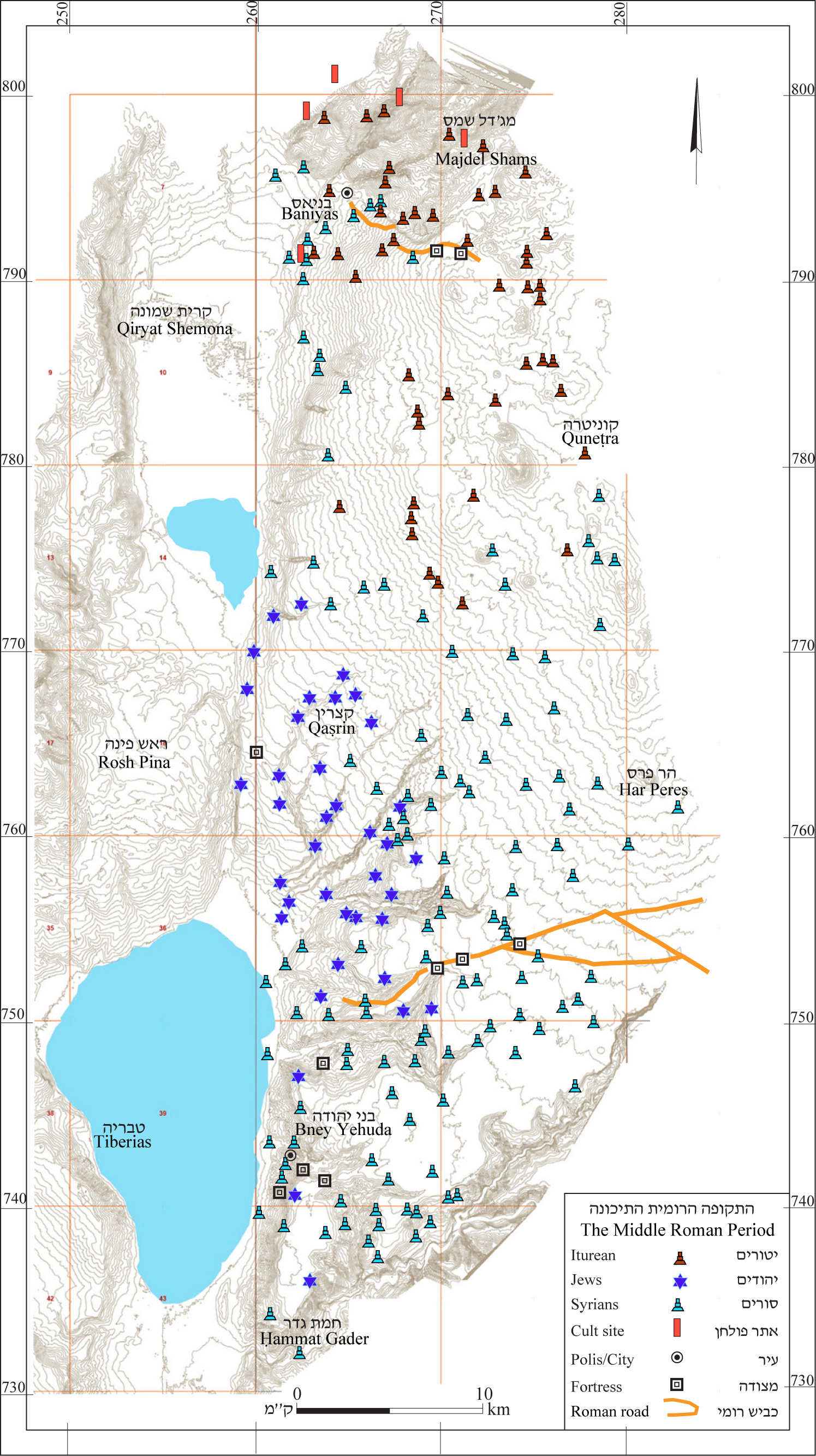

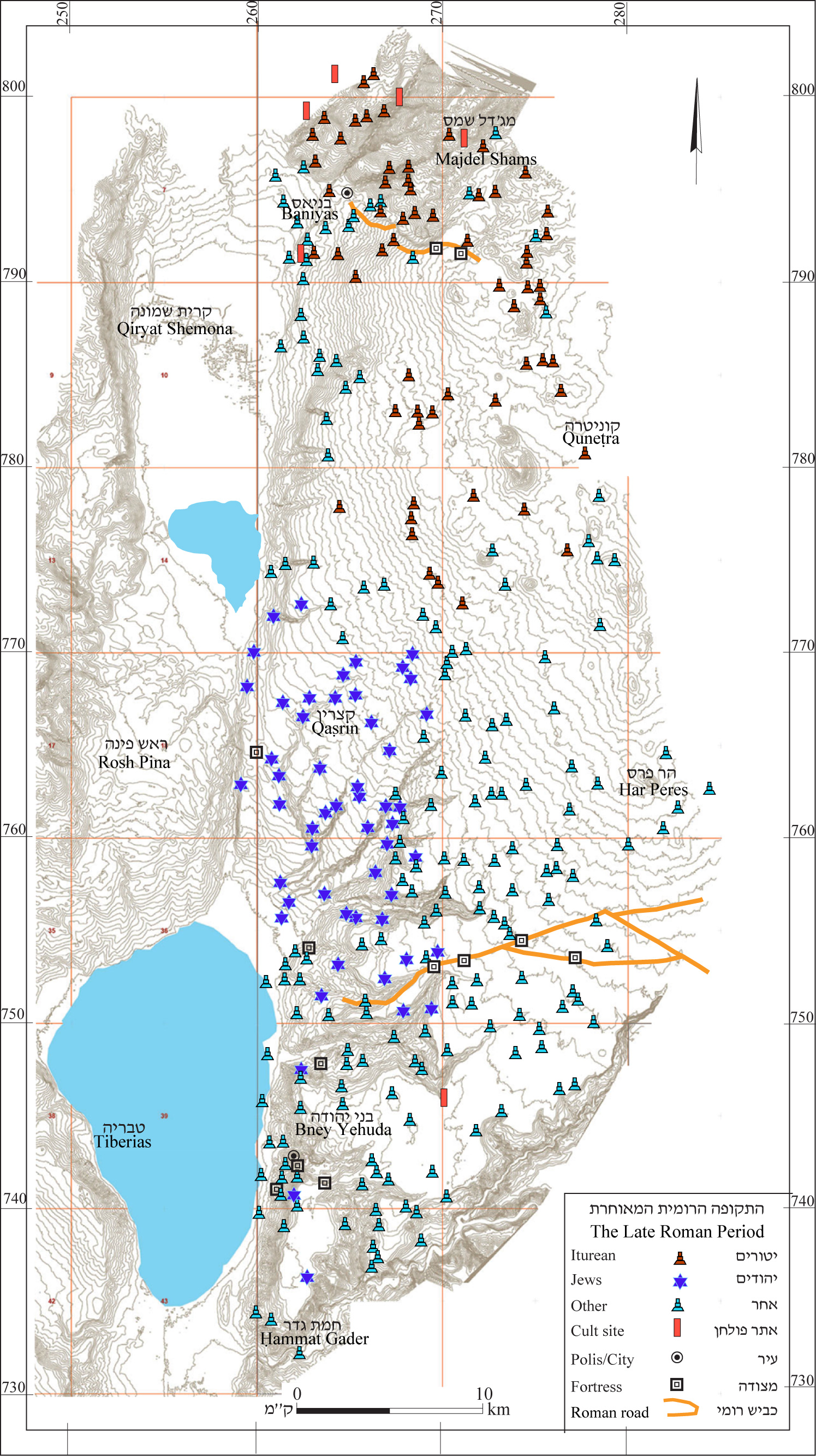

During the early Hellenistic period the Jordan River was the eastern boundary of permanent settlement. There were no such settlements anywhere in the Golan and those that have been found seem to have been inhabited by nomads or semi-nomads. The nomads only began to become sedentary in the Late Hellenistic period, in the second half of the second century BCE (see map 11).

4.10.1 The Hermon – Four sites were found from the Hellenistic period at the foot of Mount Hermon, that is, in the area of hills south of the mountain ridge. The mountainous bloc of the Hermon still had no permanent settlement. On Mount Snaim (Dan Survey) a cult enclosure was found that included enclosures adjacent to the cliffs, where coins were found dating to the second and first centuries BCE. It seems that the site served as a cult site frequented by Itureans (see below, 12.1) even before they began to settle at the foot of Mount Hermon and in the northern Golan.

Near the enclosure an Iturean settlement developed where coins were also found from this period. In excavations and in a survey no pottery vessels were found from the Hellenistic period. The vessels published by Dar (1994: Pls. 1¬¬–7) are today defined differently.

4.10.2 The Northern Golan – Remains from this period were found at 48 sites. This is double the number of sites in the area during the Iron Age. During this period the northern part, with its volcanic peaks and valleys, was settled for the first time, relatively densely.

In 34 sites (nearly 3/4 of the northern Golan's sites) Golan Ware became common (see below, 6.1). These sites were situated mainly on the low hills at the base of the Hermon and the area of the volcanic peaks and valleys. The sites were not situated by water sources, nor were cisterns found near them due to the hard-to-quarry basalt rock on which the sites were built.

These were small sites, measuring between 1 and 5 dunams. They remains of unwalled settlements in each of which were remnants of a number of structures. The structures were built of fieldstones or slightly worked stones. The walls were one stone thick.

The settlements were concentrated in clusters between 200 and 1,000 m apart. At Khirbet Zemel (Merom Golan Survey: 13) one such site was excavated, uncovering a large structure built in the second half of the second century BCE. The site was abandoned after a few decades (Hartal 2002:75–122).

The area in which these small sites were found was not settled either before or after them which made it possible to discern them. Otherwise, they would have disappeared under remains of later settlements.

The inhabitants of these hamlets did not leave clear testimony of their identity, but the similarity in time and space between them and the historical sources regarding the Itureans indicate that the inhabitants were part of the Iturean tribes (see below, 12.1, 13.1).

4.10.3 – In the western part of the northern Golan 13 sites were found from the Hellenistic period that did not contain Golan Ware. In a ruin on a steep hill east of Buq‘ata (Birket Ram Survey) no remains of Golan Were found (but only Hellenistic pottery). This site, which is surrounded by sites with Golan Ware, served as a fortress, perhaps an administrative outpost in the heart of the Iturean settlement.

The rocky Odem lava flow (see above, 2.7), separates these two groups of sites – the sites with and without Golan Ware. The lava flow was densely forested and remained unsettled until the Late Roman period.

4.10.4 The Central Golan – The 12 western sites in the northern Golan (the 13th site is located in the eastern part of the area, in the heart of the Iturean territory, see above) belong to a group of 97 settlements that extends across the central Golan. Some of the sites were built on ridges or low hills. They were surrounded by broad walls encompassing a few remnants of construction and apparently used as farms or enclosures.

The dating of these sites is problematic given that they all revealed sherds from a number of periods, and without excavation the construction cannot be attributed to one of them. Most of the sherds from the Hellenistic period that were found at these sites were produced locally rather than imported and are of low quality. Other sites revealed sherds only and the character of the settlement is unclear.

The sites extend across the area in a pattern similar to that of the Iturean settlements in the northern Golan (see above, 4.10.2). It sees therefore that the sites in the central Golan may also be attributed to sedentary processes of nomads living in the area in the early Hellenistic period. Their material culture differs from the sites in the northern Golan and they therefore seem to have been part of a different ethnic group. The historical sources give no indication of the identity of these inhabitants, which we term Syrians (see below 13.2).

4.10.5 -- At the end of the Hellenistic period the region was conquered by Alexander Jannaeus (83–80 BCE, see below, 9.3.4). The picture of settlement on the eve of the Hasmonean conquest revealed by surveys is one of meager settlement that could not withstand the might of the Hasmonean army.

Following the conquest, the area was settled by Jews and it is interesting therefore to study the fate of the Hellenistic settlements that preceded them. Analysis of the findings at the sites and their history in the Roman period indicates that the area east of the Waterfalls Road had no Jewish settlement and the original settlers continued to live there (see details in the introduction to the Qeshet and Rujem el-Hiri surveys).

West of the waterfall road settlement changed. Half the sites were abandoned and did not continue in existence in the Early Roman Period. In most of them only local pottery was found and none was known later as a Jewish settlement. It therefore seems that in those locales settlement ceased to exist after the Hasmonean conquest. In the other half of the sites settlement continued unbroken into the Roman period. In some of them, synagogues were later built. These settlements were apparently inhabited by Jews.

According to Flavius Josephus (War 1, 105; Ant. 13, 394) Gamla (Ma‘ale Gamla Survey, site no. 43) was a fortress conquered by Jannaeus. In excavations at the site no remains of a fortress were found, but hundreds of Seleucid coins were found, attesting to the existence of a settlement at this time. In contrast, hardly any sherds were found from the periods prior to the Hasmonean conquest. Gamla seems to have been another of the Hellenistic settlements defined as a fortress due to its natural fortifications.

4.10.6 In the Southern Golan – Remains were found from the Hellenistic period at 43 sites. In this area settlement was renewed as early as the Persian period (see above, 4.9) and expanded in the Hellenistic period. At three sites, Kafr el-Mā (Nov Survey, site no. 33), el-‘Āl (Nov Survey, site no. 34) and Afiq (‘Ein Gev Survey, site no. 95) remains were found attesting to an Eastern cult, the type typical of the Bashan at this time. These findings postdate the Hellenistic period but seem to reveal the presence of a Syrian population (see below, 13.2), apparently associated with settlement in the Yarmuk River valley at that time.